This page left intentionally blank

THE DEPARMENT OF DEFENSE

Indo-Pacific Strategy Report

Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region

June 1, 2019

The estimated cost of this report or study for the

Department of Defense is approximately $128,000 for

the 2019 Fiscal Year. This includes $18,000 in expenses

and $110,000 in DoD labor.

Generated on 2019June01 RefID: 0-1C9F36A

MESSAGE FROM THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE

he Indo-Pacific is the Department of Defense’s priority theater. The United

States is a Pacific nation; we are linked to our Indo-Pacific neighbors

through unbreakable bonds of shared history, culture, commerce, and

values. We have an enduring commitment to uphold a free and open Indo-

Pacific in which all nations, large and small, are secure in their sovereignty and able to

pursue economic growth consistent with accepted international rules, norms, and

principles of fair competition.

The continuity of our shared strategic vision is uninterrupted despite an increasingly

complex security environment. Inter-state strategic competition, defined by

geopolitical rivalry between free and repressive world order visions, is the primary

concern for U.S. national security. In particular, the People’s Republic of China, under

the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, seeks to reorder the region to its

advantage by leveraging military modernization, influence operations, and predatory

economics to coerce other nations.

In contrast, the Department of Defense supports choices that promote long-term

peace and prosperity for all in the Indo-Pacific. We will not accept policies or actions

that threaten or undermine the rules-based international order – an order that benefits

all nations. We are committed to defending and enhancing these shared values.

The National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy articulate our vision to

compete, deter, and win in this environment. Achieving this vision requires combining

a more lethal Joint Force with a more robust constellation of allies and partners.

Increased investments in these imperatives will sustain American influence in the

region to ensure favorable balances of power and safeguard the free and open

international order.

This 2019 Department of Defense Indo-Pacific Strategy Report (IPSR) affirms the

enduring U.S. commitment to stability and prosperity in the region through the pursuit

of preparedness, partnerships, and the promotion of a networked region.

T

Preparedness – Achieving peace through strength and employing effective

deterrence requires a Joint Force that is prepared to win any conflict from its

onset. The Department, alongside our allies and partners, will ensure our

combat-credible forces are forward-postured in the region. Furthermore, the

Joint Force will prioritize investments that ensure lethality against high-end

adversaries.

Partnerships – Our unique network of allies and partners is a force multiplier

to achieve peace, deterrence, and interoperable warfighting capability. The

Department is reinforcing its commitment to established alliances and

partnerships, while also expanding and deepening relationships with new

partners who share our respect for sovereignty, fair and reciprocal trade, and

the rule of law.

Promotion of a Networked Region – The Department is strengthening and

evolving U.S. alliances and partnerships into a networked security architecture

to uphold the international rules-based order. The Department also continues

to cultivate intra-Asian security relationships capable of deterring aggression,

maintaining stability, and ensuring free access to common domains.

Advancing this Indo-Pacific vision requires an integrated effort that recognizes the

critical linkages between economics, governance, and security – all fundamental

components that shape the region’s competitive landscape. The Department of

Defense, in partnership with other U.S. Government Departments and Agencies,

regional institutions, and regional allies and partners, will continue to diligently uphold

a rules-based order that ensures peace and prosperity for all.

Patrick M. Shanahan

Acting Secretary of Defense

This page left intentionally blank

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

Contents

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1

1.1. America’s Historic Ties to the Indo-Pacific ............................................................ 2

1.2. Vision and Principles for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific ....................................... 3

2. Indo-Pacific Strategic Landscape: Trends and Challenges ............................................ 7

2.1. The People’s Republic of China as a Revisionist Power........................................ 7

2.2. Russia as a Revitalized Malign Actor ...................................................................... 11

2.3. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as a Rogue State .......................... 12

2.4. Prevalence of Transnational Challenges ................................................................ 13

3. U.S. National Interests and Defense Strategy ............................................................... 15

3.1. U.S. National Interests ............................................................................................. 15

3.2. U.S. National Defense Strategy ............................................................................... 16

4. Sustaining U.S. Influence to Achieve Regional Objectives ......................................... 17

4.1. Line of Effort 1: Preparedness ................................................................................ 17

4.2. Line of Effort 2: Partnerships ................................................................................. 21

4.3. Line of Effort 3: Promoting a Networked Region ............................................... 44

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 53

Acronyms .............................................................................................................................. 55

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

This page left intentionally blank

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

1

1. Introduction

he Indo-Pacific is the single most consequential region for America’s future. Spanning a vast

stretch of the globe from the west coast of the United States to the western shores of India,

the region is home to the world’s most populous state, most populous democracy, and largest

Muslim-majority state, and includes over half of the earth’s population. Among the 10 largest

standing armies in the world, 7 reside in the Indo-Pacific; and 6 countries in the region possess nuclear

weapons. Nine of the world’s

10 busiest seaports are in the

region, and 60 percent of global

maritime trade transits through

Asia, with roughly one-third of

global shipping passing through

the South China Sea alone.

The United States is a Pacific

nation and has five Pacific states: Hawaii, California, Washington, Oregon, and Alaska, as well as

Pacific territories on both sides of the International Date Line, including: Guam, American Samoa,

T

“The story of the Indo-Pacific in recent decades is

the story of what is possible when people take

ownership of their future…this region has emerged

as a beautiful constellation of nations, each its own

bright star, satellites to none.”

- President Donald J. Trump, speech at the APEC CEO Summit,

November 10, 2017

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

2

Wake Island, and the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). American businesses

have traded in Asia since the 18th century, and today, within the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

(APEC), America’s annual two-way trade with the region is $2.3 trillion, with U.S. foreign direct

investment of $1.3 trillion in the region – more than China’s, Japan’s, and South Korea’s combined.

The Indo-Pacific contributes two-thirds of global growth in gross domestic product (GDP) and

accounts for 60 percent of global GDP. This region includes the world’s largest economies – the

United States, China, and Japan – and six of the world’s fastest growing economies – India, Cambodia,

Laos, Burma, Nepal, and the Philippines. A quarter of U.S. exports go to the Indo-Pacific, and exports

to China and India have more than doubled over the past decade. This is made possible by free and

open trade routes through the air, sea, land, space, and cyber commons that form the current global

system.

1.1. America’s Historic

Ties to the Indo-Pacific

The United States is a Pacific nation. Our

ties to the Indo-Pacific are forged by

history, and our future is inextricably

linked. We have contributed both blood

and treasure to sustain the freedoms,

openness, and opportunity of this region.

Our presence secures the vital sea lanes of

the Indo-Pacific that underpin global

commerce and prosperity. Our leaders,

diplomats, military forces, and businesses

helped frame and strengthen the international system of clear and transparent rules; peaceful

resolution of disputes; and the rule of law that has been vital to the region’s relative security and

growing prosperity.

The past, present, and future of the United States are interwoven with the Indo-Pacific. Our

engagement in the Indo-Pacific dates back more than two centuries, based on the pursuit of the shared

prosperity that comes from fair and reciprocal trade, open commerce, and freedom of navigation. In

1784, within months of signing the Treaty of Paris, the United States sent a trading ship, the

EMPRESS OF CHINA to inaugurate commercial ties with China. In 1804, President Thomas

Jefferson sent the explorers – Lewis and Clark – on an expedition to our Pacific Coast, which Jefferson

recognized as the gateway for increased trade and commerce. By 1817, Congress approved the first

full-time Pacific deployment of a U.S. warship. In the early 19th century, we began our relationship

with the Kingdom of Thailand and thereafter negotiated to open Japan to global trade in the 1850s.

“Starting in the Indo-

Pacific, our priority

theater, we continue to pursue many belts

and many roads by keeping our decades-old

alliances strong and fostering growing

partnerships.”

- Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick M. Shanahan,

testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee,

March 14, 2019

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

3

At the close of the 19th century, the United States established an “Open Door” policy towards China,

promoting equal opportunity for trade and commerce in China, and respect for China’s sovereignty.

In the 20th century, the United States expanded its role in the region as we confronted imperialism

and fascism and held the line against communism during the Cold War. The early 1950s marked

several milestones – the signing of the Mutual Defense Treaty between the Republic of the Philippines

and the United States in August 1951 and the signing of the Australia, New Zealand, and United States

Security Treaty in September 1951 – both of which sought to bring stability to the region. In the

seven decades that followed the Second World War, based on a foundation of the U.S. system of

alliances and our forward deployed forces, the Indo-Pacific was largely peaceful, and we helped create

the stability necessary for economic prosperity in the United States and the region.

In pursuit of partnership, not domination, the United States worked with Japan and South Korea after

the Second World War to forge alliances and stimulate an economic boom in both countries. In

Taiwan, U.S. aid helped create an open, democratic society that allowed the island to blossom into a

high-tech powerhouse. In the 1970s and 1980s, the United States invested in Hong Kong, Singapore,

and other Southeast Asian economies and supported foundational institutions like the Association for

Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the APEC Forum, and the Asian Development Bank, all

contributing to growth in the region. Simultaneously, the United States established formal diplomatic

relations with China in 1979, which facilitated economic exchange and extended America’s consistent

policy approach of a free, open market and equal trading opportunity for merchants of all nationalities

operating in the region. At the turn of the 21st century, the United States advocated for China’s

admission into the World Trade Organization, with the belief that economic liberalization would bring

China into a greater partnership with the United States and the free world.

As history has demonstrated and the future necessitates, the United States will continue to play a key

role as a force for regional stability in the Indo-Pacific in support of U.S. diplomatic and economic

aspirations. To do so, the United States must be prepared by sustaining a credible combat-forward

posture; strengthening alliances and building new partnerships; and promoting an increasingly

networked region. These actions will enable the United States to preserve a free and open Indo-

Pacific where sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity are safeguarded.

1.2. Vision and Principles for a

Free and Open Indo-Pacific

In 2017, President Trump announced our nation’s vision for a

free and open Indo-Pacific

at the

APEC Summit in Vietnam, and our commitment to a safe, secure, prosperous, and free region that

benefits all nations. This vision flows from common principles that underpin the current international

order, which has benefited all countries in the region – principles we have a shared responsibility to

uphold:

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

4

1. Respect for sovereignty and independence of all nations;

2. Peaceful resolution of disputes;

3. Free, fair, and reciprocal trade based on open investment, transparent agreements, and

connectivity; and,

4. Adherence to international rules and norms, including those of freedom of navigation and

overflight.

Our vision for a

free

Indo-Pacific is one

in which all nations, regardless of size,

are able to exercise their sovereignty free

from coercion by other countries. At

the national-level, this means good

governance and the assurance that

citizens can enjoy their fundamental

rights and liberties. Our vision for an

open

Indo-Pacific is one that promotes

sustainable growth and connectivity in

the region. This means all nations enjoy access to international waters, airways, and cyber and space

domains, and are able to pursue peaceful resolution of territorial and maritime disputes. On an

economic level, this means fair and reciprocal trade, open investment environments, and transparent

agreements between nations.

Our vision for a free and open Indo-Pacific recognizes the linkages between economics, governance,

and security that are part of the competitive landscape throughout the region, and that economic

security is national security. In order to achieve this vision, we will uphold the rule of law, encourage

resilience in civil society, and promote transparent governance – all of which expose malign influences

that threaten economic development everywhere. Our vision aspires to a regional order in which

independent nations can both defend their interests and compete fairly in the international

marketplace. It is a vision which recognizes that no one nation can or should dominate the Indo-

Pacific.

In recognition of the region’s need for greater investment, including infrastructure investment, the

United States seeks to invigorate our development and finance institutions to enable us to become

better, more responsive partners. U.S. Departments and Agencies will work with regional allies and

partners to provide end-to-end solutions that build tangible products and transfer experience.

Ultimately, the maintenance of a free and open order sustains regional development because a well-

functioning and transparent marketplace incentivizes global commercial investments that outpaces

any state’s unique resources. The United States is not alone in its pursuit of a free and open Indo-

Pacific – many of our allies and partners share these principles and values:

“The U.S. offers strategic partnerships, not

strategic dependence. Alongside our allies

and partners, America remains committed

to maintaining the region’s security, its

stability, and its economic prosperity.”

- Then-Secretary of Defense James N.

Mattis, speech at the Shangri-La

Dialogue, June 1, 2018

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

5

“We must ensure that these waters are a public good that bring

peace and prosperity to all people without discrimination into

the future.”

- Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, policy speech to the 196

th

session of the Diet

January 22, 2018

“Now what is important is to preserve a rules-based

development in the region. It’s to preserve the necessary

balances in the region.”

- President of France, Emmanuel Macron, speech during a state visit to Australia

May 2, 2018

“…rules and norms should be based on the consent of all, not

on the power of the few.”

- Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, keynote address at the Shangri-La Dialogue

June 1, 2018

“We want a rules-based system that respects the sovereignty and

the independence of every single country and a commitment

then to regional security that is always the precondition for

prosperity.”

- Prime Minister of Australia, Scott Morrison, address at the APEC CEO Summit

November 17, 2018

“Collective solutions to shared challenges in the Pacific require

strong and vibrant regionalism, with institutions that can

convert political will into action, supported by partners who

align their efforts with the region’s priorities.”

- Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs for New Zealand, Winston

Peters, address at Georgetown University

December 15, 2018

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

6

A free and open Indo-Pacific rests on a foundation of mutual respect, responsibility, priorities, and

accountability. While we unapologetically represent U.S. values and beliefs, we do not seek to impose

our way of life on others. In order to maintain the regional dynamism that benefits all, each country

in the region has a shared responsibility to contribute and sustain it – for the regional order will not

survive on its own. We will uphold our commitments, but we will rely on allies and partners to

contribute their fair share, including by investing to modernize their defense capabilities.

Advancing this vision is a whole-of-government priority that draws on the strengths and values of

American society. As Secretary of State Michael Pompeo has said, “The American people and the

whole world have a stake in the Indo-Pacific’s peace and prosperity. It’s why the Indo-Pacific must

be free and open.”

Our whole-of-government commitment was reflected at the Indo-Pacific Business Forum in 2018, as

Secretary of State Pompeo, Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, U.S. Agency for International

Development Administrator Mark Green, and other Cabinet-level officials launched new initiatives to

expand U.S. public and private investment in Indo-Pacific infrastructure, energy markets, and digital

economy. We also established new development finance partnerships with Japan, Australia, Canada,

and the European Union, supported by significant new resources and authorities in the Better

Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act or the BUILD Act, which President Trump

signed into law in October 2018. The following month, Vice President Michael Pence announced

efforts to coordinate with Japan on $10 billion in regional energy investment, establish a U.S.-ASEAN

Smart Cities Partnership, and launch a five-country partnership for electrification in Papua New

Guinea. The Vice President also announced the Indo-Pacific Transparency Initiative to help countries

attract high-quality investment and counter corruption and coercive threats to their sovereignty, by

strengthening civil society and good governance. Furthermore, the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act, a

major bipartisan legislation, was signed into law by President Trump on December 31, 2018. This

legislation enshrines a generational whole-of-government policy framework that demonstrates U.S.

commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific region and includes initiatives that promote sovereignty,

rule of law, democracy, economic engagement, and regional security.

As the region grows in population and economic weight, U.S. strategy will adapt to ensure that the

Indo-Pacific is increasingly a place of peace, stability, and growing prosperity – and not one of

disorder, conflict, and predatory economics. Embedding these free and open principles will require

efforts across the spectrum of our agencies and capabilities: diplomatic initiatives, governance capacity

building, economic cooperation and commercial advocacy, and military cooperation.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

7

2.

Indo-Pacific Strategic

Landscape: Trends and Challenges

2.1. The People’s Republic of China

as a Revisionist Power

China’s economic, political, and military rise is one of the defining elements of the 21st century.

Today, the Indo-Pacific increasingly is confronted with a more confident and assertive China that is

willing to accept friction in the pursuit of a more expansive set of political, economic, and security

interests.

Perhaps no country has benefited more from the free and open regional and international system than

China, which has witnessed the rise of hundreds of millions from poverty to growing prosperity and

security. Yet while the Chinese people aspire to free markets, justice, and the rule of law, the People’s

Republic of China (PRC), under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), undermines

the international system from within by exploiting its benefits while simultaneously eroding the values

and principles of the rules-based order. With more than half of the world’s Muslim population living

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

8

in the Indo-Pacific, the region views the PRC’s systematic mistreatment of Uighurs, Kazakhs, and

other Muslims in Xinjiang – including pervasive discrimination, mass detention, and disappearances

– with deep concern. China’s violation of international norms also extends abroad. Chinese nationals

acting in association with the Chinese Ministry of State Security were recently indicted for conducting

global campaigns of cyber theft that targeted intellectual property and confidential business and

technological information at managed service providers. China has continued to militarize the South

China Sea by placing anti-ship cruise missiles and long-range surface-to-air missiles on the disputed

Spratly Islands and employing paramilitary forces in maritime disputes vis-à-vis other claimants. In

the air, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has increased patrols around and near Taiwan using

bomber, fighter, and surveillance aircraft to signal Taiwan. China additionally employs non-military

tools coercively, including economic tools, during periods of political tensions with countries that

China accuses of harming its national interests.

The People’s Republic of China’s Military Modernization

and Coercive Actions

As China continues its economic and military ascendance, it seeks Indo-Pacific regional hegemony in

the near-term and, ultimately global preeminence in the long-term. China is investing in a broad range

of military programs and weapons, including those designed to improve power projection; modernize

its nuclear forces; and conduct increasingly complex operations in domains such as cyberspace, space,

and electronic warfare operations. China is also developing a wide array of anti-access/area denial

(A2/AD) capabilities, which could be used to prevent countries from operating in areas near China’s

periphery, including the maritime and air domains that are open to use by all countries.

In 2018, China’s placement of anti-ship cruise missiles and long-range surface-to-air missiles on the

disputed Spratly Islands violated a 2015 public pledge by the Chairman of the CCP Xi Jinping that

“China does not intend to pursue militarization” of the Spratly Islands. China’s use of military

presence in an attempt to exert de facto control over disputed areas is not limited to the South China

Sea. In the East China Sea, China patrols near the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands with maritime

law enforcement ships and aircraft. These actions endanger the free flow of trade, threaten the

sovereignty of other nations, and undermine regional stability. Such activities are inconsistent with

the principles of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Simultaneously, China is engaged in a campaign of low-level coercion to assert control of disputed

spaces in the region, particularly in the maritime domain. China is using a steady progression of small,

incremental steps in the “gray zone” between peaceful relations and overt hostilities to secure its aims,

while remaining below the threshold of armed conflict. Such activities can involve the coordination

of multiple tools, including: political warfare, disinformation, use of A2/AD networks, subversion,

and economic leverage.

During the last decade, China continued to emphasize capabilities for Taiwan contingencies. China

has never renounced the use of military force against Taiwan, and continues to develop and deploy

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

9

advanced military capabilities needed for a potential military campaign. PLA modernization is also

strengthening its ability to operate farther from China’s borders. For example, the PLA is reorganizing

to improve its capability to conduct complex joint operations, and is also improving its command and

control, training, personnel, and logistics systems. Key weapon systems deployed or in development,

include: cruise and ballistic missile systems, modern fighter and bomber aircraft, aircraft carriers,

modern ships and submarines, amphibious assault ships, surface-to-air missile systems, electronic

warfare systems, direct-ascent, hit-to-kill anti-satellite missiles, and autonomous systems.

China’s Use of Economic Means to Advance Its Strategic Interests

China is using economic inducements

and penalties, influence operations, and

implied military threats to persuade

other states to comply with its agenda.

Although trade has benefitted both

China and its trade partners, Chinese use

of espionage and theft for economic

advantage, as well as diversion of

acquired technology to the military,

remains a significant source of

economic and national security risk to all

of China’s trading partners.

While investment often brings benefits

for recipient countries, including the United States, some of China’s investments result in negative

economic effects or costs to host country sovereignty. Chinese investment and project financing that

bypasses regular market mechanisms results in lower standards and reduced opportunities for local

companies and workers, and can result in significant debt accumulation. One-sided and opaque deals

are inconsistent with the principles of a free and open Indo-Pacific, and are causing concern in the

region. For example, in 2018, Bangladesh was forced to ban one of China’s major state firms for

attempted bribery, and in the same year, Maldives’ finance minister stated that China was building

infrastructure projects in the country at significantly inflated prices compared to what was previously

agreed. Furthermore, a Chinese state-owned enterprise purchased operational control of Hambantota

Port for 99 years, taking advantage of Sri Lanka’s need for cash when its government faced daunting

external debt repayment obligations.

The United States does not oppose China’s investment activities as long as they respect sovereignty

and the rule of law, use responsible financing practices, and operate in a transparent and economically

sustainable manner. The United States, however, has serious concerns with China’s potential to

convert unsustainable debt burdens of recipient countries or sub-national groups into strategic and

military access, including by taking possession of sovereign assets as collateral. China’s coercive

behavior is playing out globally, from the Middle East and Africa to Latin America and Europe.

“B

eijing is leveraging its economic

instrument

of power in ways that can

undermine the autonomy of countries across

the region…easy money in the short term,

but these funds come with strings attached:

unsustainable debt, decreased transparency,

restrictions on market economies, and the

potential loss of control of natural

resources.”

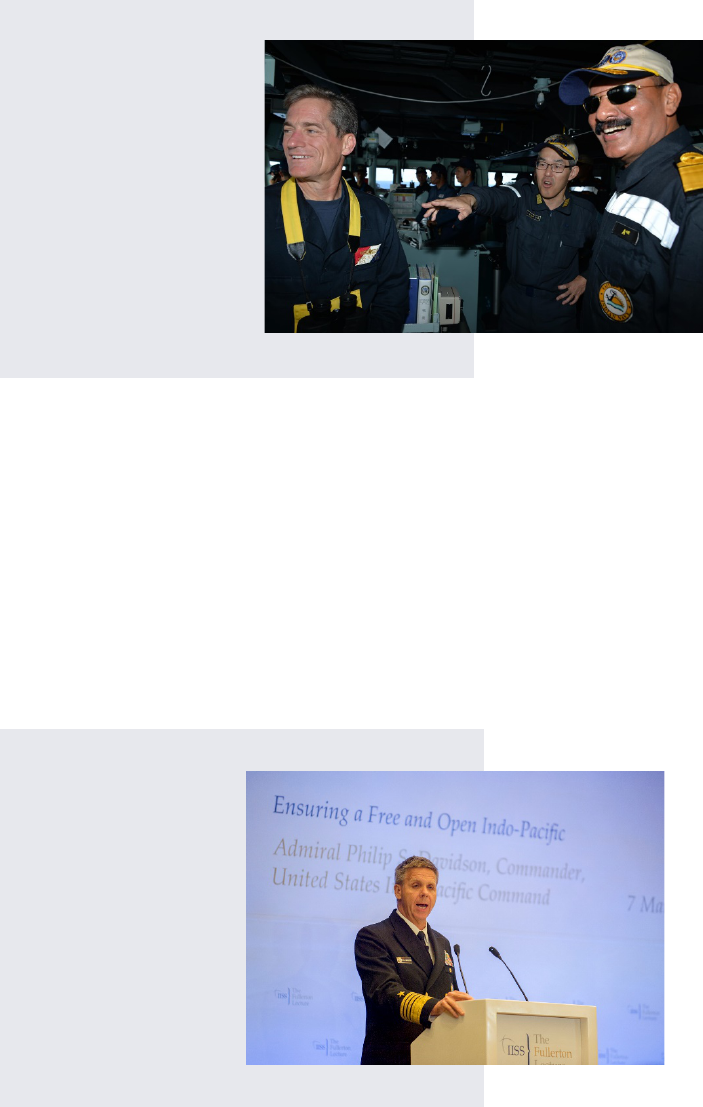

- Admiral Philip S. Davidson, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific

Command, posture testimony before the Senate Armed

Services Committee, February 12, 2019

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

10

A lack of transparency also clouds China’s activities in the

polar regions. In 2018, China announced the inclusion of the

region in One Belt One Road as the “Polar Silk Road” and

emphasized its self-declared status as a “Near-Arctic State.”

China is also expanding its engagement and capabilities in the

Antarctic, in particular by working to finalize a fifth research

station, which will diversify its presence across the continent.

Risk Reduction: Engaging China

One of the most far-

reaching objectives of the

National Defense Strategy

is to set the military

relationship between the United States and China on

a long-term path of transparency and non-

aggression.

Pursuit of a constructive, results-oriented relationship

between our two countries is an important part of

U.S. strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

As the scope of China’s military modernization and

the reach of China’s military activities expands, the

need for strategic dialogue and safe and professional

behavior consistent with international law is crucial.

When China and the PLA operate

in a manner

consistent with international norms and standards,

the risk of miscalculation and misunderstanding is

reduced. Recognizing this, our bilateral military

engagements with China, which include high-level

visits, policy dialogues, and functional exchanges, are

centered on building and reinforcing the procedures

necessary to reduce risk and prevent and manage

crises.

Through our military-to-

military engagements, the

Department of Defense will continue to encourage

China to engage in behaviors that maintain peace and

stability in the region and that support

– rather than

undermine

– the rules-based international order. We

will not accept policies or actions that threaten to

undermine this order, which has benefited all

countries in the region, including China. The United

States is prepared to support China’s choices to the

extent that China promotes long-

term peace and

prosperity for all in the Indo-Pacific, and we remain

open to cooperate where our interests align.

On October 5, 2018, President

Trump signed into law the Better

Utilization of Investments Leading

to Development (BUILD) Act. The

BUILD Act establishes a new U.S.

International Development Finance

Corporation.

This legislation

consolidates, modernizes, and

reforms the

U.S. Government’s

development finance capabilities.

Backing from the U.S. Government

can catalyze significant amounts of

private capital into emerging

markets. This model of mobilizing

private investment is vital as the

needs of developing countries are

too great to meet with official

government resources alone. The

BUILD Act prioritizes low-income

and lower middle-income countries,

where the Development Finance

Corporation’s services will have the

greatest impact. It more than

doubles the U.S. development

finance capacity from $29 billion to

$60 billion. The new authorities and

flexibility provided under the

BUILD Act will give the United

States greater agility to offer

financially sound, transparent

investment alternatives.

THE BUILD ACT

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

11

2.2. Russia as a Revitalized Malign Actor

Russia’s interest and influence in the region continue to increase through national outreach and

military modernization – in both its conventional forces and strategic forces. Despite slow economic

growth due to Western sanctions and decreasing oil prices, Russia continues to modernize its military

and prioritize strategic capabilities – including its nuclear forces, A2/AD systems, and expanded

training for long-range aviation – in an attempt to re-establish its presence in the Indo-Pacific region.

Russia’s operations and engagement throughout this region are consistent with its global influence

activities, which seek to advance Moscow’s strategic interests while undermining U.S. leadership and

the rules-based international order.

Russia’s efforts include using economic, diplomatic, and military means to achieve influence in the

Indo-Pacific region. Moscow seeks to alleviate some of the effects of sanctions imposed, following

its aggressive actions in Ukraine, by diplomatically appealing to select states in Asia and seeking

economic opportunities for energy exports. Russia also seeks to increase defense and trade relations

through arms sales in the region.

Russia is re-establishing its military

presence in the Indo-Pacific by

regularly flying bomber and

reconnaissance missions in the Sea of

Japan and conducting operations as far

east as Alaska and the west coast of the

continental United States. Russia has

also intensified its diplomatic outreach

in Southeast Asia, seeking to capitalize

on U.S.-China tensions in order to

present itself as a neutral “third

partner.” The Russian Navy has

increased its operations and reach, with

the Russian Pacific Fleet deploying ships to support operations in the Middle East and Europe, and

the Russian Baltic and Black Sea Fleets deploying to the Indo-Pacific. Russian ballistic missile and

attack submarines remain active in the region, while Russia is also undertaking efforts to modernize

its conventional forces and nuclear strike capabilities.

China and Russia collaborate across the diplomatic, economic, and security arenas. China has

increased investment in Russia's economy and Russia is one of China's top sources for energy imports.

In the security realm, China purchases advanced equipment such as Su-35 fighter aircraft and the

S-400 surface-to-air missile system from Russia. The two countries participate in bilateral and

multilateral military exercises together, including China's 2018 participation for the first time in

Russia's annual strategic command and staff exercise, VOSTOK (East) 2018. China and Russia

“For decades, the U.S. led the world in

hypersonics research – and deliberately chose

not to weaponize these systems. China and

Russia have chosen differently. Our nation

does not seek adversaries, but we will not

ignore them either. We refuse to be bound by

geography. Our new, space-

based sensor

layer will give us persistent, timely, global

awareness.”

- Acting Secretary Shanahan, remarks on the 2019

Missile Defense Review, January 17, 2019

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

12

frequently jointly oppose U.S.-sponsored measures at the United Nations Security Council. Broadly,

they share a preference for a multipolar world order in which the United States is weaker and less

influential. Russia has Arctic interests linked to its significant Arctic Ocean coastline and the

extraction of natural resources. This is witnessed by Russia’s extended continental shelf claim, and an

uptick in its military posture and investments to develop the region and the Northern Sea shipping

route, including with Chinese involvement. However, an interest in reserving Arctic resources for

littoral states may ultimately limit the extent and depth of Sino-Russian cooperation.

2.3. The Democratic People’s Republic

of Korea as a Rogue State

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea) will remain a security challenge

for DoD, the global system, our allies and partners, and competitors, until we achieve the final, fully

verifiable denuclearization as committed to by Chairman Kim Jong Un. Although a pathway to peace

is open for a diplomatic resolution of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, other weapons of

mass destruction, missile threats, and the security challenges North Korea presents are real and

demand continued vigilance. North Korea’s history as a serial proliferator, including conventional

arms, nuclear technology, ballistic missiles, and chemical agents to countries, such as Iran and Syria,

adds to our security concerns. Furthermore, the DPRK’s continued human rights violations and abuse

against its own people, including violations of individuals’ freedom of expression, remain an issue of

deep concern to the international community. The United States also continues to support Japan's

position that North Korea must completely resolve the issue of Japanese abductees, and has raised

this with North Korean authorities.

North Korea has developed an intercontinental ballistic missile intended to be capable of striking the

continental United States with a nuclear or conventional payload. In 2017, North Korea conducted a

series of increasingly complex ballistic missile launches eastward toward the United States. North

Korea did so by overflying Japan with long-range ballistic missiles. Some tests were done at highly

lofted trajectories designed to simulate flights at ranges that could reach the United States.

North Korea poses a conventional threat to U.S. allies, such as the Republic of Korea (ROK) and

Japan. North Korea has long-range artillery arrayed against the ROK – particularly the Greater Seoul

Metropolitan Area – capable of inflicting catastrophic damage on ROK civilians and large numbers

of U.S. citizens. North Korea has demonstrated willingness to use lethal force to achieve its ends. In

2010, North Korea sank the ROK corvette CHEONAN and killed 46 sailors in an unprovoked attack.

In 2010, it also shelled the ROK Yeonpyeong Island in the Yellow Sea, killing 2 civilians and 2 military

personnel and wounding 22 more.

North Korea continues to circumvent international sanctions and the U.S.-led pressure campaign

through diplomatic engagement, counter pressure against the sanctions regime, and direct sanctions

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

13

evasion. Early in 2018, North Korea exceeded its sanctioned limit on refined petroleum imports

through illicit ship-to-ship transfers. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) is working

with allies and partners to enforce United Nations Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR) by

disrupting illicit ship-to-ship transfers, often near or in Chinese territorial waters, and in the Yellow

Sea. North Korea is also engaged in cross-border smuggling operations and cyber-enabled theft to

generate revenue, while simultaneously circumventing United Nations Security Council prohibitions

on coal exports.

The Trump Administration has pursued leader-level diplomacy with North Korea for the first time,

which has highlighted unique opportunities for a brighter future for North Korea. Until North Korea

clearly and unambiguously makes the strategic decision to take steps to denuclearize, the United States

will continue to enforce all applicable domestic and international sanctions, and DoD will remain

ready to deter, and if necessary, defeat any threats to the United States, the ROK, Japan, or our other

allies and partners.

2.4. Prevalence of Transnational

Challenges

The Indo-Pacific region continues to experience a myriad of security challenges from a range of

transnational threats, including: terrorism; illicit arms; drug, human, and wildlife trafficking; and piracy,

as well as dangerous pathogens, weapons proliferation, and natural disasters. Multiple terrorist

organizations, including the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), operate in countries throughout the

region. The heavily-traveled Indo-Pacific sea lanes are targets for pirates seeking to steal goods or

hold ships and crews for ransom. Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing further challenges

regional peace and prosperity. A region already prone to earthquakes and volcanoes as part of the

Pacific Ring of Fire, the Indo-Pacific region suffers regularly from natural disasters including

monsoons, hurricanes, and floods to earthquakes and volcanic activity, as well as the negative

consequences of climate change.

Another issue of concern is weak and illiberal governance in countries. Governments that are not

responsive to the will of their people are more susceptible to malign external influence. For example,

democratic backsliding in Cambodia has taken place since 2017, when the ruling party banned

independent media and dissolved the main opposition party. Additionally, we remain concerned about

reports that China is seeking to establish bases or a military presence on its coast, a development that

would challenge regional security and signal a clear shift in Cambodia’s foreign policy orientation. In

Burma, the lack of a robust democracy has set conditions for human rights atrocities committed by

Burmese security forces in northern Rakhine State since August 2017, and has created regional

instability, with more than one million Rohingya refugees currently in Bangladesh.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

14

The United States is encouraged by positive indicators within South and Southeast Asia that

democratic institutions are on an upward trajectory and steadily improving transparency,

responsibility, and democratic values. These indicators include freedom of the press, civilian control

of the military, and free and fair elections in countries such as the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia,

each of which experienced autocratic rule in the past.

In South Asia, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are also on a positive trajectory. In Sri Lanka, after 25 years

of conflict, the government has transitioned to a constitutional, multiparty republic with a freely-

elected President and Parliament. The political system was challenged with a constitutional dispute in

late 2018. Ultimately, however, all parties respected the Supreme Court ruling that returned

democratic processes and norms, and the military remained uninvolved throughout the dispute. The

Republic of Maldives’ historic election in 2018 – with 90 percent of the eligible population voting –

ushered in the new president, who has outlined an agenda for sweeping reforms to promote free

media, an independent judiciary, and transparent public financial management.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

15

3. U.S. National Interests

and Defense Strategy

3.1. U.S. National Interests

he 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy is based upon the view that peace, security, and prosperity

depend on strong, sovereign nations that respect their citizens at home and cooperate to

advance peace abroad. It is grounded in the belief that U.S. leadership in promoting these

widely held principles is a lasting force for good in the world. As such, DoD is working to support

enduring U.S. national interests, as articulated in the National Security Strategy:

1. Protect the American people, the homeland, and the American way of life;

2. Promote American prosperity through fair and reciprocal economic relationships to address

trade imbalances;

3. Preserve peace through strength by rebuilding our military so that it remains preeminent,

and rely on allies and partners to shoulder a fair share of the burden of responsibility to protect

against common threats; and,

T

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

16

4. Advance American influence by competing and leading in multilateral organizations so that

American interests and principles are protected.

While these interests are global in nature, they assume a heightened significance in a region as

strategically and economically consequential as the Indo-Pacific.

3.2. U.S. National Defense Strategy

The 2018 National Defense Strategy guides the Department of Defense to support the National Security

Strategy in order to:

1. Defend the homeland;

2. Remain the preeminent military power in the world;

3. Ensure the balances of power in key regions remain in our favor; and

4. Advance an international order that is most conducive to our security and prosperity.

Both the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy affirm the Indo-Pacific as critical for

America's continued stability, security, and prosperity. The United States seeks to help build an Indo-

Pacific where sovereignty and territorial integrity are safeguarded, the promise of freedom is fulfilled,

and prosperity prevails for all. We stand ready to cooperate with all nations to achieve this vision.

The National Defense Strategy informs how we work with our neighbors in the Indo-Pacific and beyond,

to address key challenges in the region. The core diagnosis of the National Defense Strategy is that DoD’s

military advantage vis-à-vis China and Russia is eroding and, if inadequately addressed, it will

undermine our ability to deter aggression and coercion. A negative shift in the regional balance of

power could encourage competitors to challenge and subvert the free and open order that supports

prosperity and security for the United States and its allies and partners. To address this challenge,

DoD is developing a more lethal, resilient, and rapidly innovating Joint Force, and is increasing

collaboration with a robust constellation of allies and partners.

The challenges we face in the Indo-Pacific extend beyond what any single country can address alone.

The Department seeks to cooperate with like-minded allies and partners to address common

challenges. The United States acknowledges that allies and partners are a force multiplier for peace

and interoperability, representing a durable, asymmetric, and unparalleled advantage that no

competitor or rival can match. We seek to provide the structure that allows our respective militaries

to work together – leveraging our complementary forces, unique perspectives, regional relationships,

and information capabilities. Taking deliberate steps in these areas will allow us to improve our

collective ability to compete, deter, and if necessary, fight and win together.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

17

4. Sustaining U.S. Influence to

Achieve Regional Objectives

he National Defense Strategy directs the Department to increase lethality, to strengthen alliances,

and to expand the competitive space. In the context of the Department’s Indo-Pacific

Strategy, this translates into the pursuit of

Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a

Networked Region

.

4.1. Line of Effort 1: Preparedness

The National Defense Strategy directs the Department to employ its resources in ways that enhance the

lethality, resilience, agility, and readiness of the Joint Force. This resourcing must span near-term

force employment activities and longer-term investments to modernize and redesign the U.S. military.

The Department is developing innovative capabilities and operating concepts to address specific

operational problems. This also involves identifying new, asymmetric ways to upgrade and employ

legacy systems. Experimentation and exercises to test evolving warfighting concepts and capabilities

help create a virtuous cycle that spurs additional ideas and innovations. Many of these experiments

T

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

18

and exercises are being conducted alongside allies and partners to ensure we can test and improve

interoperability for joint and combined operations.

The National Defense Strategy implicitly

acknowledges the most stressing potential

scenarios will occur along our competitors’

peripheries. If our competitors decide to

advance their interests through force, they

are likely to enjoy a local military advantage

at the onset of conflict. In a fait accompli

scenario, competitors would seek to employ

their capabilities quickly to achieve limited

objectives and forestall a response from the

United States, and its allies and partners.

DoD initiatives on force employment, crisis

response, force and concept development,

and collaboration with allies and partners

are aimed to help address this critical challenge.

The National Defense Strategy directs the Department to

posture ready, combat-credible forces

forward

–

alongside allies and partners

– and, if necessary, to fight and win. This approach

intentionally presents competitors with a dilemma by ensuring they cannot quickly, cheaply, or easily

advance their aims through military force.

Competitors are compelled to advance

their interests through other, more benign

means – which are often subject to

internationally recognized rules or widely-

accepted state practices.

The Department is undertaking a range of

efforts to enhance Joint Force

preparedness for the most pressing

scenarios. Examples of DoD initiatives

include:

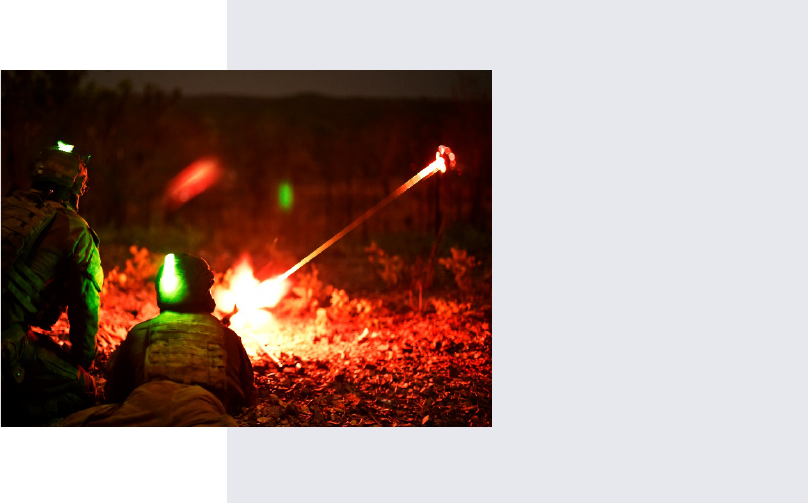

Investments in Advanced Training Facilities at the Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex to

present a more a realistic and representative training environment;

Investments in unit and depot maintenance across Air Force and Naval Aviation to achieve

an 80 percent fighter readiness goal by the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2019; and,

Investments in advanced missile defense systems interoperable with allied systems in Japan

and Australia.

“We are adapting to fight against near-peer

competitors. Our armed forces are learning

to expect to be contested throughout the

fight...We are

changing our mindset,

working to regain our advantages, and

playing to our strengths. Alliances and

partnerships are at the heart of this

competitive effort.”

- Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security

Affairs, Randall G. Schriver, speech at the Elliot School

of International Affairs, February 7, 2019

“The 2018

National Defense Strategy

’s

unified framework enables a potent

combination of teamwork, resources, and

an unmatched network of a

llies and

partners stepping up to shoulder their

share of the burden for international

security. The

National Defense Strategy

also fosters alignment wit

hin the

Department, the Interagency, industry,

and Congress.”

- Acting Secretary of Defense Shanahan, testimony to the

House Armed Services Committee, March 26, 2019

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

19

The Department is also modernizing the force to meet the demands of high-end competition.

Illustrative examples of key investments include:

Acceleration of the development and forward presence of U.S. land forces’ Multi-Domain

Task Force, utilizing Security Force Assistance Brigades to build partner capacity and

strengthen multinational teams, and expanding Pacific Pathways to deepen relationships with

U.S. allies and partners;

Strategic deterrence enhancements associated with investments in the new Columbia-class

ballistic missile submarine;

Purchase of 110 4th- and 5th-generation aircraft which will result in both capability and

capacity improvements;

Purchase of approximately 400 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missiles;

Purchase of more than 400 Joint Air-Surface Missiles – Extended Range;

Investments in two Unmanned Surface Vehicles, additional Long Range Anti-Ship Missiles,

and additional Maritime Strike Tactical Tomahawks;

Increased capacity in Anti-Surface Warfare, Anti-Submarine Warfare, and Ballistic Missile

Defense (BMD) by purchasing 10 more destroyers within the FY 2020-2024 Future Years

Defense Program;

Investment in resources to support offensive and defensive cyberspace operations; and,

Efforts to unify, focus, and accelerate the development of space doctrine, capabilities, and

expertise to outpace future threats, institutionalize advocacy of space priorities, and further

build space warfighting culture.

Current Posture in the Indo-Pacific

Defense posture is a visible manifestation of U.S. national interests and priorities abroad, and makes

up the network of U.S. forces and capabilities that are forward-deployed in the region, as well as the

interconnected bases, infrastructure, installations, and international agreements that support both day-

to-day and wartime employment of the force.

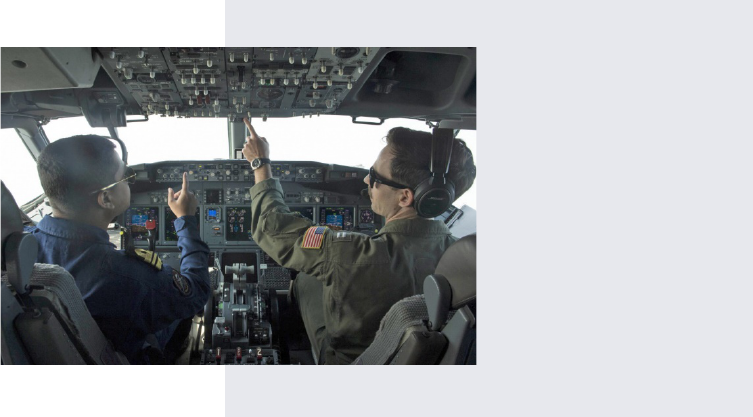

In the region, USINDOPACOM currently has more than 2,000 aircraft; 200 ships and submarines;

and more than 370,000 Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, Airmen, DoD civilians, and contractors assigned

within its area of responsibility. The largest concentration of forces in the region are in Japan and the

ROK. A sizable contingent of forces (more than 5,000 on a day-to-day basis) are also based in the

U.S. territory of Guam, which serves as a strategic hub supporting crucial operations and logistics for

all U.S. forces operating in the Indo-Pacific region. Other allies and partners that routinely host U.S.

forces on a smaller scale include the Philippines, Australia, Singapore, and the United Kingdom

through the island of Diego Garcia.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

20

Future Posture in the Indo-Pacific

To achieve our strategic objectives in the Indo-Pacific, we seek to evolve our posture and balance key

capabilities across South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania to have a more dynamic and distributed

presence and access locations across the region. For example, as announced by Vice President Pence

on November 16, 2018, the United States seeks to partner with Papua New Guinea and Australia on

their joint initiative at Lombrum Naval Base on Manus Island.

In order to overcome the tyranny of distance, posture that supports and enables inter- and intra-

theater logistics must be flexible and resilient, and the pre-positioning of equipment is critical.

Specifically, we are exploring expeditionary capabilities; dynamic basing of maritime and air forces;

special operations forces capable of irregular and unconventional warfare; anti-submarine capabilities;

cyber and space teams equipped for multi-domain operations; and, unique intelligence, surveillance,

and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities – among other investments. From leveraging existing access in

the Compact States, to pursuing co-development with our most capable allies and partners, we will

continue to forward-station leading edge technologies, such as 5th generation fighters in the Indo-

Pacific.

DoD is also developing new operating

concepts to increase our lethality, agility, and

resilience that will be further implemented

through our evolving posture. For example,

as part of the Multi-Domain Operations

concept, the U.S. Army will test Multi-

Domain Task Forces intended to create

temporary windows of superiority across

multiple domains, and allow the Joint Force

to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative. The

U.S. Army will test the Multi-Domain Task Forces through the Pacific Pathways program to determine

the right capability mix and locations. Furthermore, the Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations is

an emerging U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operating concept to provide resilience and support to

maritime operations inside contested environments. It is intended to deny adversary freedom of

action; control key maritime terrain; and support Joint Force air and maritime requirements by

operating from austere locations at a tempo that complicates adversary targeting.

In addition, DoD will continue to ensure a force posture that enables the United States to undertake

a spectrum of missions including security cooperation, building partner capacity, collaboration on

transnational threats, and joint and combined training.

“DoD’s participation in combined

military exercises has increased by

seventeen percent in the last two years,

and our Foreign Military Sales have

increased by more than sixty-five percent

in the last three years.”

- Acting Secretary of Defense Shanahan, testimony to the

House Armed Services Committee, March 26, 2019

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

21

4.2. Line of Effort 2: Partnerships

U.S. engagement in the Indo-Pacific is rooted in our long-standing security alliances – the bedrock on

which our strategy rests. Mutually beneficial alliances and partnerships are crucial to our strategy,

providing a durable, asymmetric strategic advantage that no competitor or rival can match.

Expanding our interoperability with allies and partners will ensure that our respective defense

enterprises can work together effectively during day-to-day competition, crisis, and conflict. Through

focused security cooperation, information-

sharing agreements, and regular exercises, we

are connecting intent, resources, and

outcomes and building closer relationships

between our militaries and economies.

Increasing interoperability also involves

ensuring our military hardware and software

are able to integrate more easily with those of

our closest allies and partners, offering financing and sales of cutting-edge U.S. defense equipment to

security partners, and opening up the aperture of U.S. professional military education to more Indo-

Pacific military officers.

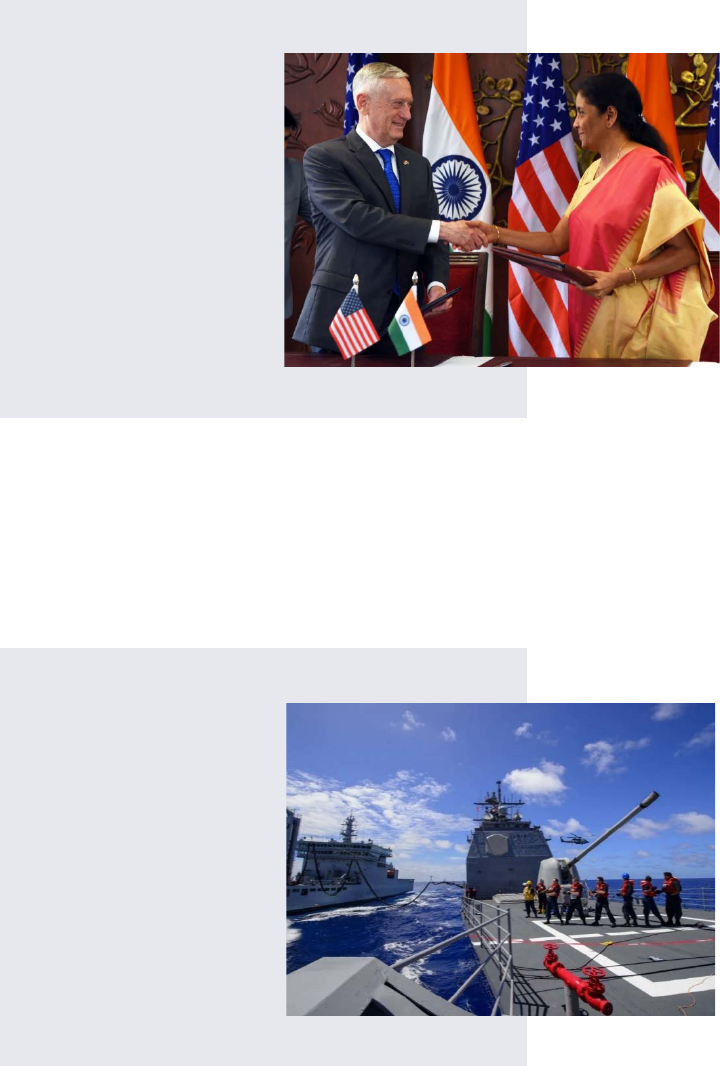

To this end, we have strengthened our alliances

with Japan, South Korea, Australia, the

Philippines, and Thailand. These alliances are

indispensable to peace and security in the region

and our investments in them will continue to pay

dividends for the United States and the world,

far into the future. We have also taken steps to

expand partnerships with Singapore, Taiwan,

New Zealand, and Mongolia. Within South

Asia, we are working to operationalize our Major

Defense Partnership with India, while pursuing

emerging partnerships with Sri Lanka, the

Maldives, Bangladesh, and Nepal. We are also

continuing to strengthen security relationships

with partners in Southeast Asia, including

Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia, and

sustaining engagements with Brunei, Laos, and

Cambodia. In the Pacific Islands, we are enhancing our engagement to preserve a free and open Indo-

Pacific, maintain access, and promote our status as a security partner of choice. Efforts to maintain a

free and open Indo-Pacific have also brought us closer to key allies, including the United Kingdom,

France, and Canada, each with their own Pacific identities.

“Our network of allies and

partners is a force multiplier for

peace and interoperability.”

- 2018 National Defense Strategy

BURDEN SHARING

The National Security Strategy calls on the

United States to pursue cooperation and

reciprocity together with our allies,

partners, and aspiring partners.

Cooperation means sharing responsibilities

and burdens. The United States expects

our allies and partners to shoulder a fair

share of the burden of responsibility to

protect against common threats. When we

pool resources and share responsibility for

our common defense, our security burden

becomes lighter and more cost-effective.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

22

Modernizing Alliances

JAPAN

The U.S.-Japan Alliance is the cornerstone of peace and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific, with the United

States remaining steadfast in its commitment to defend Japan and its administered territories. As the

security dynamic in the Indo-Pacific evolves, however, it is imperative that the U.S.-Japan Alliance

adapt to meet the challenges that

threaten our security and shared

values. Whether countering

North Korea’s rogue behavior, or

long-term strategic competition

with China and Russia, we must

pursue concrete objectives that

preserve the alliance as our

asymmetric advantage.

The National Defense Strategy clearly

articulates that the Department

will prioritize and strengthen our

alliances, identifying the U.S.-

Japan Alliance as a critical

relationship. Japan’s 2018 National Defense Program Guidelines echoes a similar message, reinforcing

the fundamental fact that the security interests of both the United States and Japan are closely

intertwined. Given the urgency to address new threats, trends, and technologies, we have already seen

progress in operational

cooperation, mutual asset

protection, and bilateral planning.

Maintaining the technological

advantage the alliance needs to

fight and win against our

adversaries is also a top-tier

priority, with the Department

continuing to streamline Foreign

Military Sales (FMS) to Japan and

other allies, pursue co-

development opportunities, and

deepen cooperation in the cyber

and space domains.

FOREIGN MILITARY SALES

The National Security and National Defense Strategies have

elevated FMS as a tool of first resort in strengthening

alliances and attracting new partners. Conventional Arms

Transfer Policy and Security Cooperation reforms have

focused our ability to improve the efficiency and

effectiveness of FMS. We have been successful in

reducing costs, improving processing times, and

minimizing policy hurdles to make technology more

available to a larger group of partners.

Acting Secretary

Shanahan with

Japanese Minister

of Defense

Takeshi Iwaya, at

the Pentagon,

January 16, 2019.

Photo by Master Sgt. Angelita

Lawrence

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

23

POSTURE: JAPAN

U.S. forces in Japan are an essential component of our posture in the region. To meet shared threats,

advance common interests, and fulfill our obligations under the U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual

Cooperation and Security – a key enabler for maintaining a free and open Indo-Pacific region – the

Department remains steadfast in its commitment to deploy our most capable and advanced forces to

Japan. The Government of Japan

contributes financially to the

stationing of U.S. forces in Japan

through a Special Measures

Agreement. This strategic

contribution directly supports the

operational readiness of U.S. forces

in Japan.

The Department assigns

approximately 54,000 military

personnel to Japan, in the U.S.

Navy’s Seventh Fleet, U.S. Marine

Corps’ III Marine Expeditionary

Force, 3 Air Force wings, and

smaller U.S. Army and Special

Operations units. Some of the more

advanced capabilities stationed in

Japan include the F-35, MV and

CV-22, and the USS RONALD

REAGAN, our only forward

deployed aircraft carrier. BMD

assets are also tightly woven into our

force posture in Japan, including

AEGIS Destroyers, sophisticated

BMD radar systems, and a

PATRIOT firing unit to counter the

ballistic missile threat. Enhancing

operational cooperation between

the U.S. forces and Japan Self

Defense Forces (JSDF) is also a

priority, as outlined in the 2015

Guidelines for U.S.-Japan Defense

Cooperation. Bilateral presence

operations throughout the Indo-

Pacific region, mutual asset

GUAM AND THE COMMONWEALTH OF

THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS

(CNMI)

The Department is modernizing its force posture in

Guam, in keeping with Guam’s position as the

westernmost territory of the United States and a strategic

hub for our joint military presence in the region. We are

establishing a Marine Air Ground Task Force of 5,000

U.S. Marines in Guam starting in the first half of the

2020s as a central feature of the U.S.-Japan realignment

plan. In Guam, we have some of the most significant

ammunition and fuel storage capabilities in the Indo-

Pacific. The addition of rotational maritime lift in Guam

will increase the reach of our combat power in the

Western Pacific. At Anderson Air Force Base, we have

established an active Army Missile Defense capability in

response to increasing threats, and maintain a continuous

bomber presence and ISR capability. In the CNMI we

have air, surface, and subsurface training capabilities and

we are taking steps to ensure we will have ready joint

forces and opportunities for increased multilateral

training.

The Government of Japan has already provided more

than $2 billion of a $3.1 billion commitment for

construction of facilities for the U.S. Marine Corps

realignment. The U.S. Government will fund the balance

of construction, estimated at $8.6 billion, and is working

toward an outcome that enhances our Indo-Pacific

posture, bolsters our security commitments in the region,

and directly benefits Guam.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

24

protection missions, and bilateral exercises are just a few areas of operational cooperation that U.S.

forces and the JSDF collaborate on to advance our shared objectives.

The realignment of U.S. forces in Japan contributes to a regional force posture that is geographically

distributed, operationally resilient, and politically sustainable. We have already made substantial

progress on this initiative. Examples include the movement of the U.S. Navy’s Carrier Air Wing Five

to Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni, the stationing of JSDF units on U.S. Air Force and Army bases,

and the return of more than 10,000 acres of land in Okinawa to the Government of Japan. Future

steps include the completion of the Futenma Replacement Facility and the return of U.S. Marine

Corps Air Station Futenma, as well as the consolidation of our remaining bases and the return of

additional land in Okinawa, Japan.

REPUBLIC OF KOREA

The United States remains steadfast in its

commitment to the defense of the

Republic of Korea (ROK). The U.S.-

ROK Alliance is the linchpin of peace and

prosperity in Northeast Asia, as well as the

Korean Peninsula.

The Department is continuing its work

with the ROK Ministry of National

Defense to transition wartime operational

control for Combined Forces Command

(CFC) from a U.S. Commander to a ROK

Commander. To achieve this, the DoD

and the ROK Ministry of National Defense are investing in critical military capabilities to ensure our

combined readiness to meet any threat to the alliance. The United States and the ROK are also

working to enhance alliance capabilities in the fields of space, cyberspace, and missile defense, along

with efforts to counter weapons of mass destruction.

Together, the United States and the ROK are constantly improving our ISR capacity; developing a

robust, tiered BMD; fielding appropriate command and control assets; acquiring necessary inventories

of critical munitions; and enhancing the tools to prevent, deter, and respond to cyber attacks.

The United States and the ROK continue combined training through command post exercises, as well

as field training exercises to ensure the readiness and combat proficiency of combined forces on the

Peninsula and in the region. The Department is also working to revitalize the United Nations

Command, which contributes to peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula through oversight and

maintenance of the 1953 Armistice Agreement.

“The alliance between South Korean and

American forces is ironclad – forged in

blood, shaped over 65 years of combined

military operations and training, and

hardened by the crucible of war. Shared

sacrifice and mutually agreed principles

underpin our alliance and ens

ure it

endures the winds of change.”

- Commander of U.S. Forces Korea, General Robert B.

Abrams, testimony to the Senate Armed Services

Committee, February 12, 2019

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

25

POSTURE: REPUBLIC OF KOREA

The U.S-ROK combined force – unique among bilateral U.S. military relationships – is a robust

deterrent to aggression on the Korean Peninsula. As we sustain readiness for any conflict, the United

States and the ROK also remain committed to the final, fully verified denuclearization of North Korea

and enduring peace on the Korean Peninsula.

The Department has three

unique commands on the

Korean Peninsula: U.S. Forces

Korea (USFK), the CFC, and

the United Nations Command.

The ROK hosts 28,500 U.S.

service members and their

families to units including the

U.S. Eighth Army and 2nd

Infantry Division, Seventh Air

Force, U.S. Marine Corps

Forces Korea, U.S. Special

Operations Command-Korea,

and Commander, Naval Forces

Korea. Advanced capabilities

stationed in South Korea include two fighter wings of F-16 and A-10 aircraft; a major U.S. Army

prepositioned stockpile; a combat aviation brigade; a field artillery brigade; advanced ISR units; and a

headquarters for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The ROK continues to invest more in its defense

over the past 15 years than it did in decades

before, spending over 2 percent of its gross

domestic product on defense and increasing

foreign military procurements from the United

States, such as the KF-16 and PATRIOT

battery upgrades, AH-64E Apaches, the

F-15K, RQ-4 Global Hawk variants, and the

F-35A Joint Strike Fighter. Seoul also has

future procurement plans for the P-8, advanced

munitions, upgrades to PAC-3 missiles, and

F-16 fighters – all of which will increase

interoperability with the United States.

Significant improvements in U.S. Force posture during 2018 include adding essential munitions, BMD

systems, and pre-positioned wartime stocks. The United States continues to work with the ROK to

create an interoperable BMD architecture that addresses the ballistic missile threat from North Korea.

In 2017, the United States deployed a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense battery to the ROK.

“The force is sufficiently postured to

deter aggression and defeat any

adversary, if necessary. We continue to

train at echelon to maintain the

readiness required to translate a strong

military posture into decisive victory on

short notice.”

- General Abrams, testimony to the Senate Armed

Services Committee, February 12, 2019

Acting Secretary of

Defense Shanahan

hosts the South

Korean Minister of

National Defense

Jeong Kyeong-doo

at the Pentagon,

April 1, 2019.

Photo by Master Sgt. Angelita

Lawrence

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

26

The United States and the ROK have agreed to a 10th Special Measures Agreement that will enable

the ROK to help offset the cost of stationing U.S. forces on the Korean Peninsula. The Special

Measures Agreement will ensure essential readiness related personnel and activities, including the

contributions of 9,000 South Korean national employees of USFK serving in crucial roles of public

safety, health care, emergency response, and quality-of-life delivery operations.

Our joint efforts in military construction and modernization ensures our forces are postured, prepared,

and properly set for the future. The Land Partnership Plan and the associated Yongsan Relocation

Plan are bilateral agreements that provide the foundation for streamlining USFK’s footprint while

returning facilities and valuable land to the ROK Government for future development. In 2018,

USFK and United Nations Command Headquarters relocated both commands from U.S. Army

Garrison Yongsan to U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys in Pyeongtaek, joining U.S. Eighth Army and

2nd Infantry Division in new state-of-the-art facilities on the largest DoD facility outside of the

continental United States. By consolidating capability in Pyeongtaek, on facilities built mostly with

ROK funds, we maximize our ability to uphold U.S. security commitments, return large portions of

downtown Seoul to the Korean people for economic development, and improve the quality of life for

our Service members and their families. Since 2003, USFK has returned 49 sites to the ROK while

simultaneously moving the majority of our forces and families away from the demilitarized zone and

closer to major air and sea ports.

AUSTRALIA

U.S. and Australian forces have shared the battlefield in every major conflict since the First World

War and celebrated their “First Hundred Years of Mateship” in 2018. For more than a century, we

have conducted joint and coalition operations, training and exercises, intelligence cooperation, and

capability development. The United States and Australia share a commitment to building on the

interoperability of our armed forces, collaborating to ensure the security of the Indo-Pacific region

into the future, and seeking innovative ways to adapt to new threats.

Australia is providing forces in Iraq for the counter-ISIS fight as trainers, force protection, and

advisors. Australia’s significant commitment to a stable and secure Afghanistan is also helping

modernize our alliance through its contribution to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-

led Resolute Support Mission to train, advise, and assist the Afghan National Defense and Security

Forces. Australia is also a key contributor to the UNSCR enforcement operations to bring North

Korea into compliance with its international obligations and serves as a significant partner to the

Philippines in building counter-terrorism capacity.

Both the United States and Australia are strengthening security in the Indo-Pacific through more

deliberate coordination of the policies and priorities underlying regional engagements by promoting

interoperability to address new threats, increasing focus on the Pacific Islands, and leveraging the U.S.-

Australia force posture initiatives and the unique exercising and training opportunities created in the

process.

Indo- Pacific Strategy Report

27

The Department is also partnering with Australia in cyber, space, and defense science and technology

domains. Together, we are building upon our long-established defense intelligence partnership