Healthy cities — walkability as a component of health-promoting urban planning and design. © 2016 Minh-Chau Tran. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/),

permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

11

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Healthy cities — walkability as a component of

health-promoting urban planning and design

Minh-Chau Tran

Institute of City Planning and Urban Design, University of Duisburg-Essen, 45141 Essen, Germany

Abstract: Health impairments due to inactivity are related to the car-oriented urban development of recent decades, along

with sedentary lifestyles. A health-maintaining environment must therefore not only reduce direct health risk factors

(pathogenic concept), but also contribute to health chances that may indirectly support health (salutogenic concept).

Walking has been identified as the most influenceable behavior; it is also the most environmental-friendly mode of

transport, social and health. From the planning view, the concept of walkability therefore aims at a built environment

facilitating physical activity. It is increasingly recognized that walkability has become an important topic in the field of

planning, urban design and health, since the built environment affects certain behaviors. From practice, concrete guidance

is demanded as to the type of urban design features to be captured or applied to evaluate the walkability or to create active

cities. The measurement of features of the built environment plays a special role in this context, but also the question of

how research results can reach policies as well as planning and building practice.

Keywords: health-promotion, urban design, urban planning, built environment, walkability, physical activity

Correspondence to: Minh-Chau Tran, Institute of City Planning and Urban Design, University of Duisburg-Essen, 45141 Essen, Germany;

Email: minh[email protected]

Received: February 13, 2016; Accepted: April 15, 2016; Published Online: June 2, 2016

Citation: Tran M-C, 2016, Healthy cities — walkability as a component of health-promoting urban planning and design. Journal of

Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress, vol.1(1): 11–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.18063/JSUPP.2016.01.006.

1. Introduction — Reconnecting Urban Plan-

ning and Public Health

he rapid increase of people living in cities

will be among the most important global health

issues of the 21st century

[1]

. Though in devel-

oped countries, as well as in many developing coun-

tries, the standard of living and economic prosperity

are increasing compared to the past, it is not always

and necessarily going hand in hand with the “quality

of life” and health of the population. Improved urban

supply and disposal systems, as well as living condi-

tions, have led to health enhancement of the urban

population. This — in combination with the progress

in different sectors such as health care, hygiene, nutri-

tion and working conditions — resulted in an increase

of life expectation. This surely might be a merit of the

traditionally close collaboration between the profes-

sions of urban planning and public health with the

common goal of reducing harmful impacts of indu-

strialization and urbanization.

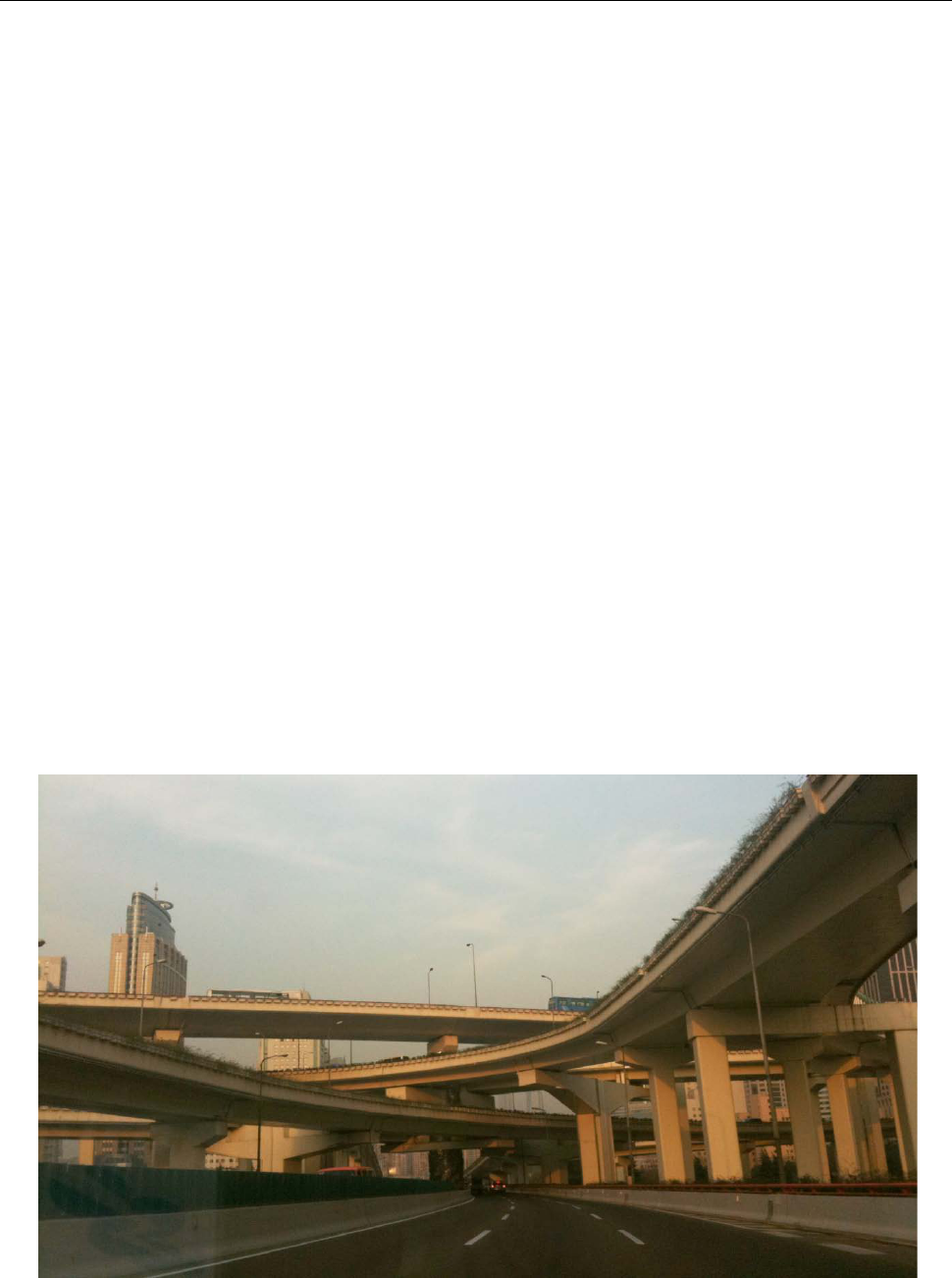

According to the planning ideology of the car

oriented city in the 1960s, urban spaces have since

then been created with negative impact on health. At

the same time the close connection between both pro-

fessions broke off. Public health concentrated on indi-

vidual biomedical factors. Urban planning lost sight of

its original mission of tackling the health problems of

the least well-off and merely focused on spatial and

functional structures

[2]

. Health experts have now iden-

tified new primary health risks and adverse health ef-

fects that are closely connected to car-oriented urban

development in recent decades

[3]

. Yet, still many parts

of the world currently follow the traditional car friend-

T

Healthy cities — walkability as a component of health-promoting urban planning and design

12 Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1

ly city model with separation of functions and sprawl,

ignoring human scale and resulting in oversized roads

for motorized individual traffic. Since in many coun-

tries development and modernity are still associated

with technology, external financing favors large con-

struction projects such as urban highways, elevated

pedestrian pathways or skyways

[4]

(Figure 1).

This has resulted in unhealthy living environments

due to congestion, noise emissions, street fatalities,

increase of CO

2

and global greenhouse gases, and at

the same time support unsustainable, inactive life-

styles and inequity in street use. In cities of northern

China, levels of the most dangerous particulates reach

almost 50 times of the maximum limits stipulated by

the World Health Organization

[5]

. As a result, there

has been a shift from primarily infectious diseases to

more non-communicable chronic diseases such as

cardiovascular disease, diabetes or neurological dis-

orders

[6]

. There is also a lack of social interactions in

cities that evidently increases mortality risk signifi-

cantly

[7]

. Moreover, a continuous increase of obesity

around the world within the last decades is associated

with the built environment

[8,9]

. This is not only ob-

served in Western countries but also in China, Viet-

nam or India

[10]

. “Yet health policies in most rapidly

urbanizing countries remain dominated by dis-

ease-focused solutions that ignore the social and

physical environment. As a result, health problems

persist, and health inequities have increased”

[1]

. From

an individual point of view, health development leads

apart from reduced life span to reduced quality of life.

From a social point of view, it is the high finan-

cial burden of the health care system, which leads to

growing research in this field.

Because negative health developments still proceed

in many developing countries which run parallel to

urbanization processes, even though with a time lag

compared to developed countries, the challenges, ef-

fects and health outcomes worldwide are expected

to be comparable in spite of differences in spatial

scale and size. However, the strategies and policies to

tackle these health issues are different due to culture

and mentality.

The causes for health and illnesses cannot be ex-

plained on an individual level anymore. Rather, it is

found that health occurs as an interaction between

individual, social and built environment. Individual

measures alone are not sufficient to allow urban pop-

ulation to lead a healthy lifestyle. Rather, fundamental

environmental changes are necessary in order to per-

manently establish healthy behavior for all

[11]

. A

health-maintaining environment must therefore not

only reduce direct health risk factors such as noise and

particular matter (pathogenic concept), but also con-

tribute to health chances that may indirectly promote

healthy behavior (salutogenic concept) on which the

Figure 1. Car-oriented urban development in Shanghai (Source: Alexander Schmidt)

Minh-Chau Tran

Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1 13

focus of this article is explained here. The health pro-

moting city not only stays an issue for the health sec-

tor but is also part of the mission statement of a sus-

tainable urban development.

This article primarily deals with the concept of

walkability and outlines an overview of the walkabil-

ity research. Based on current studies, it is exempli-

fied by the type of features of the built environment,

the level of walkability that can be identified, the

challenges of creating activity-friendly cities and

neighborhoods, and approach of the research results

that are able to satisfy the policy as well as planning

and urban design practices.

2. Conceptual Issues – Health-Related Factors

in Urban Planning

A comprehensive understanding of urban structure,

design of spaces and city planning processes as critical

determinants of population health is crucial

[12]

. On

World Health Day 2010, the World Health Organiza-

tion recommended the following five calls to action

to build a healthy and safe urban environment: (i)

promote urban planning for healthy behaviors and

safety, (ii) improve urban living conditions, (iii) en-

sure participatory urban governance, (iv) build inclu-

sive cities that are accessible and age-friendly, and (v)

make urban areas resilient to emergencies and disas-

ters

[13]

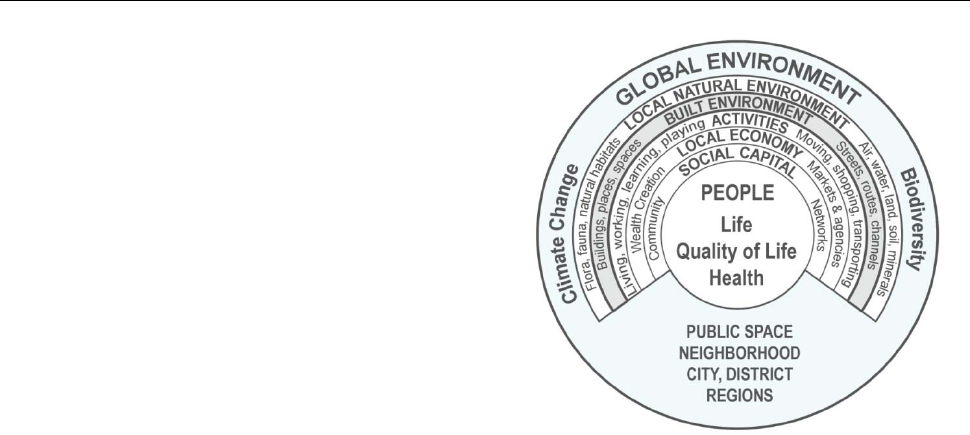

. To address the lack of a conceptual framework

for integrating health into spatial planning decisions,

Barton

[14]

developed a conceptual model of settle-

ments that places human health and well-being at its

heart (Figure 2). The model combines an ecosystem

analysis expressing the relationship between people

and their environment with a public health approach,

which identifies the relevant social and environmental

determinants of health. This does not include heredity

factors since the focus of this health map is on the

social and environmental determinants of health

[14]

.

Regarding the effects of the built environment on

health, numerous evidence-based findings exist

[16,17]

.

For example, individual behavior and lifestyle are af-

fected by the presence, safety and quality of routes

and uses, by the density and structure of cities, and by

the distances to certain destinations. Broader envi-

ronmental conditions, including air, water, soil and

climate, are affected by planning policy and can

even be critical to health in some contexts

[18]

. A study

lead by WHO identified twelve health objectives for

planning, related to equity, exercise, social cohesion,

housing, work, accessibility, food, safety, air quality,

Figure 2. Health map. Own illustration based on Barton

[14]

developed from the model by Dahlgren and Whitehead

[15]

.

water, earth and climate

[19]

. This provides an agenda

for analyzing health impacts. A holistic approach for

health promoting urban planning should ideally con-

sider all of these factors and at the same time integrate

their interrelations.

Since this article represents the urban design pers-

pective, further focus lies on the sphere of the built

environment

[20]

. The built environment of a city in-

corporates not only buildings, streets, squares, and

green spaces as well as urban planning features like

land use, density, infrastructures and transportation

systems, but also urban structures and urban form.

3. From Car-oriented to Health-promoting Ac-

tive Cities and Neighborhoods

It has been proved that health derives from the inte-

raction between the individual and its social and built

environment

[19,21]

. Car-oriented urban spaces increa-

singly impede daily physical activity, coincidently

with our modern inactive lifestyles. The lack of green

open spaces, for sojourn and physical activity and safe

traffic areas for environmental-friendly local mobility

negatively affects the health and quality of life of city

dwellers. This results from a minimum of daily wa-

lks

[22]

. In many countries 80% of adults do not achieve

the recommended level of activity of 150 minutes of

exercise a week

[23]

. Correlations between the lack of

exercise and a high risk, for example, of developing

cardiovascular disease and cancer, are well known

[24]

.

Lack of physical activity is the developed world's

fourth largest risk of death after smoking, high blood

Healthy cities — walkability as a component of health-promoting urban planning and design

14 Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1

pressure and overweight/obesity

[25]

.

Walking has been identified as the movement be-

havior that can be influenced most easily and is also

the most common and simplest form of physical activ-

ity. It is increasingly recognized that the pedestrian is

not only an important object of traffic planning and

that walking is more than just another form of mobili-

ty; it is also a human behavior and thus has interna-

tionally become an important topic in the field of ur-

ban planning, urban design, mobility and health, since

the built environment affects behavior

[26]

. Recently,

more and more interdisciplinary research is dealing

with interrelations among activity-friendly urban

spaces and long-term benefits for society

[21]

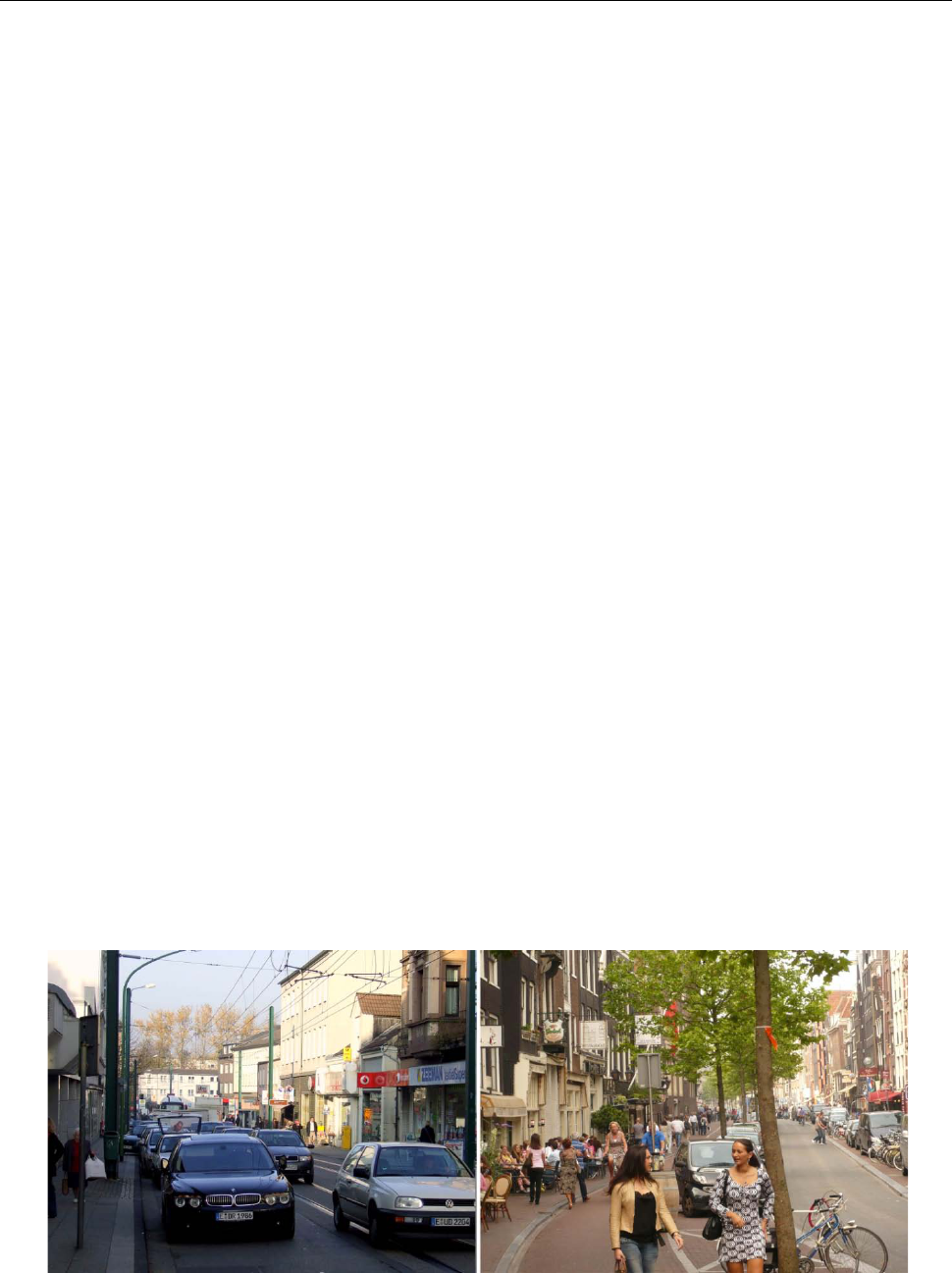

. At the

same time, the readiness to develop new forms of mo-

bility and the reclaiming of urban spaces for pede-

strians and cyclists seem to give additional impetus to

this trend (Figure 3).

3.1 Walkability — More than Just Walking Friendly

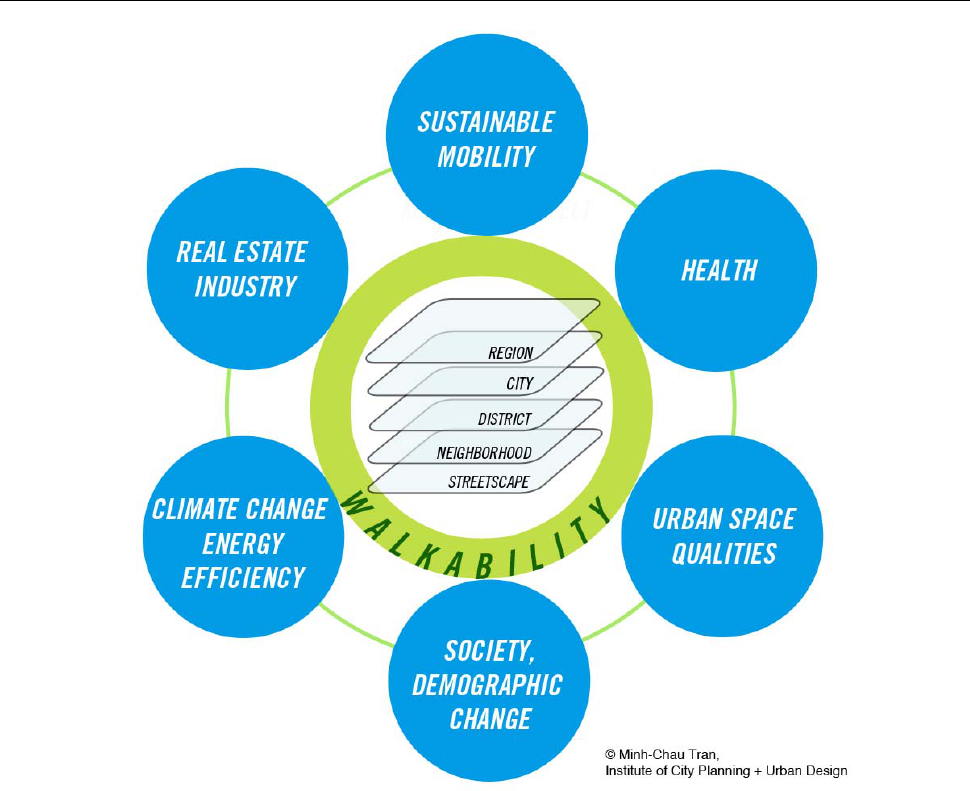

The concept of walkability pursues a holistic approach

and aims at an environment encouraging active living

taking into account different spatial levels (macro and

micro levels). Generally, walkability describes the

level of pedestrian-friendly urban structures and spac-

es motivated and promoted active mobility

[27,28]

. De-

sign recommendations is not limited to using individ-

ual measures such as the improvement of traffic lights

or speed limits, because it is not only about security

for pedestrian traffic, but at the same time about the

creation of urbanity, identification and quality of life

through activity-friendly public urban spaces.

People who live in a pedestrian-friendly designed

environment participate much more in social life and

have greater confidence in their environment. That

proved a significant gain in “social capital” and thus

a better quality of life

[29]

. To date, we speak of walka-

bility and its different dimensions

[30]

(Figure 4). Aga-

inst this backdrop walkability is understood as a com-

prehensive approach for a livable sustainable city and

does not only mean walk-friendliness.

3.2 Walkability Research — A Multidisciplinary Field

Walkability as a research field was first initiated in

public health from concerns about the constantly ris-

ing obesity rates worldwide. Since the 1990's multi-

disciplinary walkability research has accumulated,

namely of the Health Sciences as well as the traffic

planning and later also of urban planning, especially

in English-speaking countries

[9,31]

. The idea of walk-

ing to be facilitated by good planning and urban de-

sign is also not new in many countries, e.g. in Ger-

many

[32–34]

. Although overall awareness of the impor-

tance of health in the last three decades has grown in

the field of urban planning, walking basically seemed

to play a minor role as a mode of transport in planning.

Because today in developing countries there is suppo-

sedly no direct acute health hazard emanating from

the built environment compared to the industrialization

phase, “urban planning can apparently (...) only broach

health problems as design problems (...) where health

is objectified, measurable and generalizable”

[35]

.

Walkability research in the fields of traffic planning

and health science is therefore focusing strongly on

the measurable extent or likelihood of walking in rela-

tion to different environmental characteristics based

on analysis models

[36,37]

. Measuring walking behavior

serves to inform policy and planning and to evaluate

its impact

[38]

. An increased interest in research on an

international level was very promising, reinforced by

Figure 3. Car-oriented street space versus people-oriented street space. (Source: Institute of City Planning and Urban Design)

Minh-Chau Tran

Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1 15

Figure 4. The dimensions of walkability. (Source: Institute of City Planning and Urban Design)

new evaluation methods and technologies

[38]

. This re-

search showed, for example, interrelations between

population density, connectivity, mixed use and walk

frequency

[9]

.

These results underpin empirical studies in objec-

tively measurable ways. However, they fall short as

urban walking areas are too complex for quantifica-

tions. Walking does not comprise only purpose-ori-

ented utilitarian walking, but allowed the utmost spon-

taneity and communication of all types of mobility.

Therefore, in the field of urban design there are

studies that examine the measurable and qualitative

characteristics on site

[39]

. Here, subjective qualities such

as human scale, transparency and linking street spaces

are measured with the objective to establish opera-

tional definitions for measuring urban design qualities

of these spaces. These qualities are closely linked

to basic urban principles that were formulated in var-

ious senior key publications in the fields of architec-

ture and urban design, and are still valid to this

day

[25,40–42]

. By observational studies they deal pri-

marily with the influences of urban space on behavior

patterns and social activities in order to better under-

stand the use of public spaces.

Finally, the consideration of objectively measured

environmental characteristics and the subjective per-

ception of the environment are essential for a more

comprehensive understanding of walkability.

3.3 Balance Matters — Urban Design Characteris-

tics to Evaluate Walkability and for the Planning of

Walkable Neighborhoods

Despite the increase in evidence-based knowledge and

the desire to actively intervene with the help of study

results for a change in urban planning policies and

practices, there seem to be a lack of clarity about the

urban features needed in the weighting to promote

active behaviors. Urban planners and policymakers

Healthy cities — walkability as a component of health-promoting urban planning and design

16 Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1

call for clear instructions from research regarding

principal urban design features that promote health

and healthy behavior, such as walking

[43]

. In addition,

it was often unclear about the appropriate methods

that should be selected or are present to capture these

characteristics best. There are a number of different

methods to measure the characteristics of the built

environment. This can be divided into three categories:

(i) interviews or questionnaires that capture primarily

perceptions, (ii) methods that collect (existing) data,

often by using geographic information system (GIS)

analysis, and (iii) systematic observations or audit

tools

[37,44]

.

The Five “D”s

Empirically proven criteria for walkability are the five

“D”s: Density, Diversity, Design, Destination accessi-

bility, Distance to transit

[39,45]

(Table 1).

The five “D”s have the greatest impact when they

act together. It therefore requires a balance of residen-

tial use, jobs, services and facilities in the vicinity of

public transport stops and within walking radii and a

fitting of all these elements in a fine-grained urban

environment and in a cityscape that improves walking

experience on street scale

[39,45]

. In relation to large-

scale, car-oriented urban structures in the United States

or Australia the density and diversity of European

towns and cities have considerable potential to pro-

mote small-scale mobility in everyday life. Their

structures and designs can serve as best examples.

4. Case Study on Neighborhood Scale Linking

Built Environments with Health Effects

The current case study presented exemplifies a me-

thod applied on neighborhood scale about the connec-

tion of built environment features and health effects

that could be assessed and evaluated.

This recent study by Sallis and colleagues

[46]

aimed

at proving the evidence about the connection of built

environments and moderate to intense physical activi-

ty by studying different built environments across 14

cities in ten middle-income and high-income countries.

It was the largest study so far. Through linking objec-

tively measured physical activity with objectively

measured built environment features, it was observed

that urban environmental factors account for large

differences in the physical activity levels of adults.

The analyses were based on the International Phys-

ical Activity and Environment Network (IPEN) adult

study and included 6822 adults aged 18–66 years.

Neighborhoods divided into four different stratifica-

tion groups were identified in order to maximize vari-

ation in neighborhood walkability and socioeconomic

status (SES): (i) Higher walkability and higher SES,

(ii) higher walkability and lower SES, (iii) lower wal-

kability and higher SES, and (iv) lower walkability

Table 1. Overview of the five “D”s, the associated indicators and possible methods of measurement. (Source: Compiled on the basis

of Ewing/Cervero (2010)

[39]

, Campoli (2012)

[45]

)

Criterion Indicator Method

Density

Degree of density, e.g., population, housing units or jobs per hectare or km

2

As a measure, which is applicable to many of the characteristics of the built environment, density describes the

intensity of a specific element or an activity.

e.g., GIS analysis

Diversity

Level of diversity in land use and thus of people and places (Land use mix)

Diversity, or the mix of uses, creates a dense texture of destinations. A good mix of uses as to how residents can

find more everyday products and services in their neighborhoods, and do not need to travel by car. The degree

of diversity, or how many uses co-exist in one location and how close they are to each other, is crucial.

e.g., GIS analysis

Design

Presence and design of streets, walking and cycling paths as well as interconnecting streets

To lower vehicle miles traveled (VMT) two strategies are important here: The network of streets (connectivity)

in order to shorten travel distances, and creating pedestrian- and cycle-friendly roads to improve the quality of

the journey. Intersection density has been identified as one of the most important indicator of the built

environment for reducing VMT. Among the “D” variables street design is most difficult to measure due to

complexity. It includes, for example, road and sidewalk width, safe crossing opportunities, street accompanying

trees, shelter at bus stops and first floor design.

e.g., GIS analysis,

on-

site assessment

by walk audits and

checklists,

interviews, surveys

Destination

accessibility

Distance or duration to key destinations of daily supply

The accessibility of destinations, or how close places are located to destinations people go to most regularly, is

most strongly associated with reduced VMT. This variable may be measured by the distance to a central

business district, the supply center or by how many jobs or attractions are within a three-minute drive or a

fifteen-minute walk

e.g., GIS analysis,

test walks

Distance to

transit

Distance from the starting point to the nearest public transport stop

Distance to transit, or public transit accessibility, is the key to attract more passengers. A dense network of

routes and stops will ensure that public transport users have no long distances to travel to or from stops.

e.g., GIS analysis,

testing, on-site ass-

essment

Minh-Chau Tran

Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1 17

and lower SES. The level of walkability was de-

fined by using the neighborhood walkability index

score. This included the variables of net residential

density, intersection density and mixed land use de-

veloped within a geographic information system.

Physical activity was measured by using electronic

accelerometers that recorded motion every minute,

which is a valid and accepted method. Participants

completed a survey and wore the accelerometers for 4

to 7 days around the waist, except during sleep, swim-

ming and showering. Study dates ranged from 2002 to

2011 across countries.

Built environment variables were created with GIS

software. Buffers around each participant’s home

within 0.5 km and 1 km, reachable by the street net-

work, were defined to estimate accessible neighbor-

hood features. The comparable variables used were:

net residential density, street intersection density, retail

and civic land use ratio to buffer area, public transport

density, public park density and distance to nearest

transport.

Statistical analysis was carried out to link environ-

mental variables and physical activity (min/day) by

implementing generalized additive mixed models.

Four variables showed significant positive association

with higher physical activity levels: higher residential

density; higher number of intersection accessible to

pedestrians; higher density of public transport; and

more parks within walking distance (0.5 km) that were

free and open to all. Mixed use was surprisingly not

related to physical activity though this factor is one of

the more consistent correlates of physical activity.

This is explained by the lack of small scale data and

the limitations of GIS measures where the data were

based on a number of parcels of land, not on a number

of shops or offices which might be more strongly re-

lated to use frequency and thus higher activity level.

Further results showed that adults living in walka-

ble neighborhoods were 68–89 min/week more phys-

ically active than those in the least activity-friendly

neighborhoods. This shows that built environments

are able to assist residents to achieve 45%–59% of the

recommended 150 min/week

[23]

. This study showed

“clear evidence for the role of the built environment in

enhancing physical activity levels for entire popula-

tions, across socioeconomic classes and cultures, and

thereby preventing non-communicable disease.”

[47]

5. How to Build Places that Facilitate Active

Mobility in Everyday Life?

An important goal is to have these evidence-based res-

earch results embedded into planning and design prac-

tice. The objective of planning science in this field is,

inter alia, to identify those characteristics and urban

design configurations that prompt the decision to move

actively and that influence the perception of pede-

strians, and to operationalize them for the planning

and urban design practice. Besides raising awareness

for this topic, other necessary steps include identifica-

tion and assembling of stakeholders and alliance par-

tners, planning/projection, implementation and operation.

5.1 Methods to Obtain Addressee-focused Arguments

The challenge, among other things, is to convincingly

point out the link between, on the one hand certain

urban design and open space configurations, and on

the other hand the actual impact on health-promo-

ting behaviors and further social gains. In this policy,

the following requirement plays a crucial role: “To

what extent the growing social importance of health

can be reflected in urban planning itself, (...) ulti-

mately probably depends on whether the health aspect

receives political support from local decision-mak-

ing bodies.”

[48]

Urban planners and policy makers themselves have

pointed out that much practical evidence is required to

evaluate the effectiveness of existing planning poli-

cy

[43,49]

. Therefore, one of the next steps could be to

develop metrics to evaluate “success”, also economi-

cally, to address other parties such as investors, future

residents and public representatives who make finan-

cial decisions, “What is the value added by designing

for health? (…) – does it include enhanced productiv-

ity, longer lives, lower health care expenditures, more

robust tax bases?”

[17]

5.2 Awareness of Walkability Through Appropriate

Participation Formats

At the same time, the question was crucial, as to de-

termine whether the abstract results of these mea-

surements can be applied in the concrete building de-

sign practice and whether the needs of different popu-

lation groups can be considered. The difficult task

of building physical activity, such as walking, into

people’s daily lives, is therefore likely to require in-

novative participation and communication formats and

the appropriate tools in the future. Therefore, not only

the aspect of spatial and building design, but also the

common design of spatial processes with the local

people on site is crucial to create health-promoting

cities within the meaning of the Toronto Charter

Healthy cities — walkability as a component of health-promoting urban planning and design

18 Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1

(2010)

[50]

: “Make the healthy choice the easy choice!”

Political education is a prerequisite when it comes to

mobilizing planning and policy on the one hand and

the people on the other for implementing health-pro-

moting construction measures. The first step is to raise

awareness among the participants and stakeholders for

this topic.

5.3 Walk Audits, Temporary Urban Interventions

and “Natural Experiments”

A powerful tool for raising awareness is systematic

on-site assessments (walk audits), guided by an audi-

tor, for example, an expert from the urban planning

field, so that elaborated suggestions for improvement

are adapted to the individual conditions of each area.

There are walk audit tools consisting of checklists,

questionnaire tools or computer-assisted audit tech-

niques. A new set of digital tools for collecting data of

the built environment and linking it with measured

people’s health outcomes as a reaction to certain urban

situations offers new possibilities; specially designed

apps on mobile phones and biosensors allowed for

recording participants’ movements and measuring

their excitement, interest, and levels of stress, locating

and visualizing them in a map such as in the experi-

ments conducted by Ellard and Montgomery in New

York, Berlin and Mumbai.

[51]

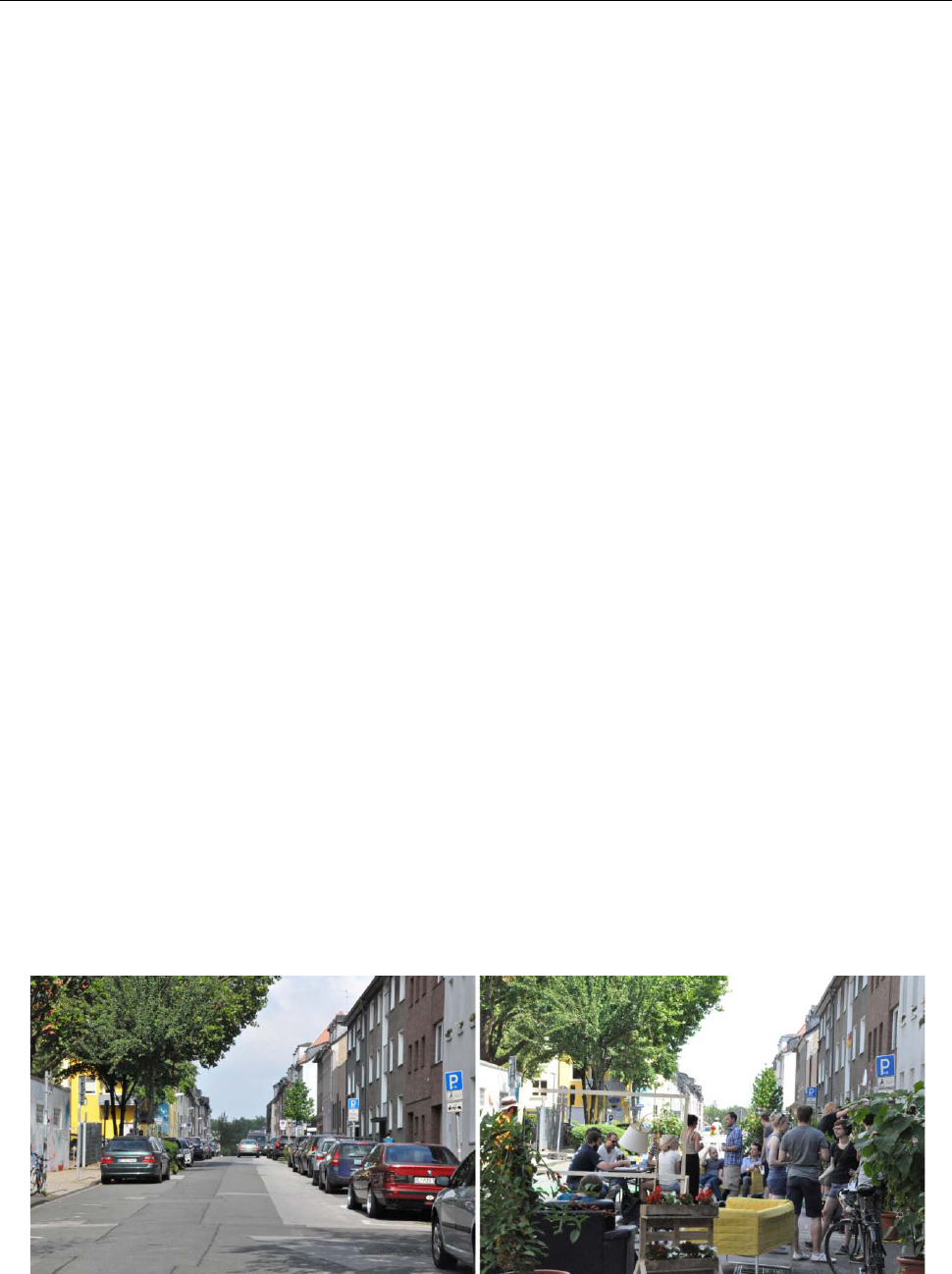

Urban temporary intervention in public space is

another instrument of procedural urban development

seen as part of planning and participation processes.

This could give impetus to possible long-term health-

promoting behavioral change. Temporary street clo-

sures for automobiles, for example, can appear as a

test and preliminary step to future project opportuni-

ties, how streets can be designed to be more pede-

strian-friendly and thus inviting the people to reside

(Figure 5). With relatively few resources conditions

can be created for more security and social participa-

tion in public space. People can perceive, feel and live

their new space. Temporary conversions can activate

streets and present local retail and community facili-

ties. Through this process there will be a direct feed-

back from the users, and the effectiveness of the mea-

sures can be examined. In practice, these temporary

changes have often given impetus to a permanent

transformation: What had initially been regarded as an

experiment by the city was rebuilt into a permanent

solution following a positive evaluation. This method

could meet “long-standing calls for ‘natural experi-

ments’ in research.”

[17]

Windows of opportunities should be recognized and

utilized by these ideas as be linked to existing initia-

tives or urban redevelopment projects. Thus, this pro-

vides a specific opportunity for research to carry out

“natural experiments” to evaluate before and after

effects concerning health impacts, even if transport

policy or structural changes are not primarily aimed at

changing health behavior. These pre- and post-evalua-

tions provide valuable information, which typical

cross-sectional studies are unable to provide.

6. Conclusion

Apparently it is a worldwide phenomenon that plan-

ning and urban development are not committed

enough to health issues but still to the automobile and

to urban mobility, which is dealt in a highly sectoral

way and not considering social and health implica-

tions. In the end, for all sectors dealing with the plan-

ning and design of health-promoting cities and neigh-

borhoods it is a matter of pursuing the common goal

of reducing health threatening conditions, promoting

human health, and at the same time increasing the

Figure 5. Urban intervention “Urban Living Room” in Essen — before / after. (Source: Institute of City Planning and Urban Design)

Minh-Chau Tran

Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1 19

quality of life for urban population. Cooperative res-

earch approaches based on findings in urban planning,

urban design, transport planning, health sciences and

socio-spatial research represent an important step in

the efforts of creating healthier and more livable cities

and neighborhoods.

But for those research findings to reach those in

practice, who plan, design and build our cities, neigh-

borhoods and street spaces, appropriate investment

and communication formats and other support as by

urban sociologists, educators and communication scie-

ntists are required. Strategic measures beyond mere

changes in the built environment may also call for

educational campaigns in public health, the exchange

of information about health promoting urban planning

as also the use of new media, changes in legal require-

ments, the encouragement of public dialogue and crea-

ting opportunities for participation and co-deliberation.

After 60 years of implementing the concept of a

car-friendly city, it is time to return to a health-pro-

moting and human oriented city. Facing energy short-

ages and social justice, it is important to apply a hu-

man scale in order to create healthy living and work-

ing conditions for all.

Conflict of Interest and Funding

No conflict of interest was reported.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO), 2010, Hidden cities:

unmasking and overcoming health inequities in urban

settings, viewed July 13, 2014,

<http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/publications/hiddencit

ies_media/who_un_habitat_hidden_cities_web.pdf>

2. Corburn J, 2004, Confronting the challenges in recon-

necting urban planning and public health. American

Journal of Public Health, vol.94(4): 541–546.

3. Frumkin H, Frank L and Jackson R J, 2004, Design,

planning and building for healthy communities, in Ur-

ban Sprawl and Public Health, Island Press, Washington

D.C.

4. Tiwari G, 2015, Time for new mobility paradigm: chal-

lenges and opportunities facing pedestrian infrastructure

in cities. Presentation at the WALK21 Conference, viewed

October 22, 2015, Academic OneFile database.

5. South China Morning Post, 2015, Smog in northeast

China at nearly 50 times World Health Organisation

safe limits, viewed November 10, 2015,

<http://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/1877

282/smog-northeast-china-nearly-50-times-world-health

-organisation>

6. Omran A R, 1971, The epidemiologic transition. A

theory of the epidemiology of population change. Mil-

bank Memorial Fund Quarterly, vol.3(4): 731–757.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00398.x.

7. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith T B and Layton J B, 2010, Social

relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review.

PLoS Medicine, vol.7(7): e1000316.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316.

8. Giles-Corti B, Macintyre S, Clarkson J P, et al. 2003.

Environmental and lifestyle factors associated with

overweight and obesity in Perth, Australia. American

Journal of Health Promotion, vol.18(1): 93–102.

9. Saelens B E, Sallis J F and Frank L D, 2003, Environ-

mental correlates of walking and cycling: findings from

the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures.

Annals of Behavioral Medicine, vol.25(2): 80–91.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_03.

10. Chelala C, 2015, Obesity outpaces growth in China, The

Japan Times, viewed October 24, 2015,

<http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2015/05/10/commen

tary/world-commentary/obesity-outpaces-growth-in-china/>.

11. Syme L, 2004, Social determinants of health: the com-

munity as an empowered partner, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, viewed June 25, 2014,

<http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/jan/03_0001.htm>

12. Corburn J, 2009, Towards the Healthy City: People, Place

and the Politics of Planning, MIT Press, Cambridge.

13. World Health Organization (WHO), 2010, Why urban

health matters, viewed July 13, 2014,

<http://www.who.int/world-health-day/2010/media/whd

2010background.pdf>

14. Barton H, 2005, A health map for urban planners — to-

wards a conceptual model for healthy, sustainable set-

tlements. Built Environment, vol.31(4): 339–355.

15. Dahlgren G and Whitehead M, 1991, Policies and

strategies to promote social equity in health: back-

ground document to WHO — strategy paper for Europe,

Institute for Future Studies, Stockholm, Sweden.

16. Designed to move, n.d., viewed September 30, 2015,

<http://www.designedtomove.org>

17. Bassett E M, 2014, Designing the Healthy Neigh-

borhood: Deriving Principles from the Evidence Base,

Hart Howerton, University of Virginia.

18. Wilkinson R and Marmot M, (eds.) 1998, The solid facts:

social determinants of health. WHO Regional Office for

Europe, Copenhagen.

19. Barton H and Tsourou C, 2000, Healthy Urban Pla-

nning, World Health Organisation, Europe, Spon Press,

Europe.

20. Dockery D W, Pope C A III, Xu X, et al. 1993, An asso-

ciation between air pollution and mortality in six U.S.

Healthy cities — walkability as a component of health-promoting urban planning and design

20 Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1

cities. The New England Journal of Medicine, vol.329:

1753–1759.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199312093292401.

21. Sallis J F, Cervero R B, Ascher W, et al. 2006, An eco-

logical approach to creating active living communities.

Annual Review Public Health, vol.27: 297–322.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.

102100.

22. MiD (Mobility in Germany), Institute for Applied Social

Sciences Ltd. and German Aerospace Center 2010, Mo-

bility in Germany 2008, Report Structure – Volum e –

Emissions – Trends. Bonn and Berlin, viewed June 3,

2015, German,

<http://www.mobilitaet-in-deutschland.de/pdf/MiD2008

_Abschlussbericht_I.pdf>

23. Robert Koch Institute, 2010, Health reporting in Ger-

many. Facts and figures: results of the study “Health in

Germany 2009”, Berlin, German.

24. Lee I M, Shiroma E J, Lobelo F, et al. 2012, Impact of

physical inactivity on the world’s major non-commu-

nicable diseases. The Lancet, vol.380(9838): 219–229.

http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9.

25. World Health Organization (WHO) 2009: 10, viewed

June 3, 2015,

<http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_stat

istics/EN_WHS09_Full.pdf>

26. Gehl J, 2010, Cities for People, Island Press, Wash-

ington D.C.

27. Robertson-Wilson J and Giles-Corti B, (eds) 2010,

Walkability, neighbourhood design, and obesity, in Ob-

esogenic Environments: Complexities, Perceptions and

Objective Measures, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford: 21–39.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118786611.ch3.

28. Tran M C and Schmidt J A, 2014, Walkability from the

perspective of urban and transport planning, in J

Bucksch and S Schneider, Walkability — The Handbook

for Promotion of Physical Activity in the Community,

Hans Huber, Bern, 61–71, German.

29. Rogers S H, Halstead J M, Gardner K H, et al. 2010,

Examining walkability and social capital as indicators of

quality of life at the municipal and neighborhood scales.

Journal of Applied Research in Quality of Life, vol.6(2):

201–213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11482-010-9132-4.

30. Walljasper J, 2013, Walking as a way of life movement

for health & happiness, viewed April 22, 2016,

<http://everybodywalk.org/media_assets/WalkingAsAW

ayOfLife1_Final.pdf>

31. Cervero R and Kockelman K, 1997, Travel demand and

the 3ds: density, diversity, and design, Transportation

Research Part D: Transport and Environment, vol.2(3):

199–219.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1361-9209(97)00009-6.

32. Vogler P and Kühn E, (eds.) 1957, Medicine and urban

design, A Handbook for Healthy Urban Design, Volume

1 and 2, Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich, Berlin,

Vienna, German.

33. ILS Institute of Regional and Urban Development Re-

search of North Rhine-Westphalia, (eds.) 1979, in Space

for Pedestrians, Dortmund: 1–3, German.

34. ILS Institute for Regional and Urban Development Re-

search of North Rhine-Westphalia, (eds.) 2001, in Pede-

strian Traffic — A Planning Guide for Practice, Series

Bausteine 24, Dortmund, German.

35. Rodenstein M, (eds) 1996, City and hygiene since the

18th century, in Does City Make us Sick? Dealing with

Health and Disease, Dölling and Galitz, Hamburg, German.

36. Lee C and Moudon A V, 2006, Correlates of walking for

transportation or recreation purposes. Journal of Physi-

cal Activity and Health, vol.3(sup.1): 77–98.

37. Brownson R C, Hoehner C M, Day K et al. 2009, Mea-

suring the built environment for physical activity: state

of the science. American Journal of Preventive Med-

icine, vol.36(4): S99–S123.e12.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.005.

38. Sauter D, Hogertz C, Tight M, et al. 2010, Introduction,

COST 358 Pedestrians´ Quality Needs: measuring walk-

ing, PQN final report — Part B4: documentation, Euro-

pean Science Foundation, viewed September 11, 2010,

<http://www.walkeurope.org/uploads/File/publications/

PQN%20Final%20Report%20part%20B4.pdf>

39. Ewing R and Cervero R, 2010, Travel and the built en-

vironment. Journal of the American Planning Associa-

tion, vol.76(3): 265–294.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944361003766766.

40. Appleyard D, 1981, Livable Streets, University of Cali-

fornia Press, Berkeley.

41. Whyte W, 1980, The Social Life Of Small Urban Spaces,

Project for Public Spaces Inc.

42. Jacobs J, 1961, The Death and Life of Great American

Cities, Vintage Books, New York.

43. Allender S, Cavill N, Parker M et al. 2009, ‘Tell us

something we don’t already know or do!’ — the res-

ponse of planning and transport professionals to public

health guidance on the built environment and physical

activity. Journal of Public Health Policy, vol.30(1):

102–116.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2008.43.

44. Tran M C, 2014, Walkability — assessment of structural

and urban design features on macro and micro level, in

Koch M K, Krüger V, Schmidt A (eds), Competition

Energy Efficient City — Urban Development and Mo-

bility. Energy and Sustainability 4, Lit Publisher, Ber-

lin-Münster-Vienna-Zurich-London, German.

45. Campoli J, 2012, Made for Walking — Density and

Minh-Chau Tran

Journal of Sustainable Urbanization, Planning and Progress (2016)–Volume 1, Issue 1 21

Neighborhood Form, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy,

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

46. Sallis J F, Cerin E, Conway T L, et al. 2016, Physical

activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities

worldwide: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet,

vol.387(10034): 2207–2217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01284-2

47. Goenka S and Andersen L B, 2016, Our health is a func-

tion of where we live, The Lancet, vol.387(10034):

2168–2170.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00348-2

48. Rodenstein M, (eds.), 1994, Will the life in our cities be

healthier? in Health in the City. Models-experiences-

perspectives, Fischer paperback publisher, Frankfurt/

Mainz: 39–55, German.

49. Koohsari M J, Badland H and Giles-Corti B, 2013, (Re)

Designing the built environment to support physical ac-

tivity: bringing public health back into urban design and

planning. Cities, vol.35: 294–298.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.07.001.

50. Global Advocacy Council for Physical Activity, Interna-

tional Society for Physical Activity and Health, 2010,

The Toronto Charter for Physical Activity: a global call

for action. Journal of Physical Activity and Health,

vol.7(s3): S370–S373.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jpah.7.s3.s370.

51. Ellard C and Montgomery C, 2013, Testing, Testing!: a

psychological study on city spaces and how they affect

our bodies and minds, BMW Guggenheim Lab, viewed

April 15, 2015,

<http://thehappycity.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/TESTI

NG_TESTING_BMW_GUGGENHEIM_LAB_2013.pdf>